AMY TENBRINK: Let’s talk gender and villainy, especially in speculative fiction. What does it mean to you for a woman or nonbinary person to be a villain? What does it mean for you for Ayt Madashi, the Pillar of the Mountain in your Green Bone Saga, to be a villain? To you, her creator, what is her villainy? And was she always a woman—did gender come into play as you developed her character?

FONDA LEE: For me, the concept of the fictional villain is simply this: someone whose goals and actions are in direct opposition to those of the protagonist. Throughout history, it’s typically men who are held up as heroes, both in real life and in fiction, while women are presented in supporting roles or as villains. Yes, there are many notable female heroes, and far more now than there used to be, but I suspect that if you look across the history of literature and storytelling, they’re outnumbered by the famous villainesses who stand in the way of the man—just think of every wicked witch or seductress ever written. When there’s a woman or nonbinary person opposing a man, I’m frankly inclined to think they probably have their own very understandable reasons for their villainy.

Moral ambiguity is something that you’ll find in almost all of my work. I’ve often said that I don’t really write heroes and villains because I could just as easily and sympathetically have written the story from the perspective of the antagonist. Ayt Madashi is a good example of this. She’s a villain in the story because she’s such a strategic and tenacious rival to the protagonist Kaul family, but when you consider her rationale, it makes an awful lot of sense. I envisioned Ayt Mada as a woman right from the start. Her toughness, ruthlessness, and need to be publicly flawless are all a result of her climbing to power in a highly male-dominated culture. She murdered her way into power—but how many men have done the same? What choice did she have, when she was clearly the most capable and qualified leader, and was passed up because she was a woman? She has a plan that she truly believes is the best way forward for the country—one that involves her being the one in charge. Like many powerful authoritarian leaders, she can be a hero to some and a villain to others.

AMY: While we’re on the topic of your epic, dangerous Green Bone Saga, I’d love to know your view on the feminism of the world you’ve built. Your wuxia fantasy is full of hypermasculinity and violence, some of which is permitted women, but there’s an underlying thread that women must transgress to achieve Pillar-level leadership, which is perhaps why my heart skips every time Kaul Shae and Ayt Mada interact—and I gasped aloud at that moment in Jade War (you know which one, but no spoilers here). What do you hope your work says about feminism and the roles of women in society?

FONDA: My goal is to write speculative fiction with as much verisimilitude as possible. I’m not trying to shape the world to my liking or to something in particular, but to hold up a mirror to our own world. I want the places, the people, and the societies I write to feel entirely real to the reader, and that extends to the roles of women. To me, that means presenting a range of women and the roles they take on in a hypermasculine culture—everything from the willfully ignorant and passive mob wife (Shae’s mother, Kaul Wan Ria), to the supportive partner and soft power behind the throne (Wen), to the exceptional strongwoman who succeeds by outcompeting the men (Ayt Mada).

Verisimilitude to me also means not leaning into the hypersexualized fantasy stereotypes of female villains. There’s a scene in Jade City when Anden meets Ayt Mada for the first time and thinks to himself that she looks like an ordinary woman in comfortable pants reading reports in her office. (Because that’s exactly what a female CEO or stateswoman or Green Bone clan leader would do!)

Another thing that I wanted to do was write a fantasy story that was not static in terms of cultural development. The Green Bone Saga takes place in the modern era, and there are forces of globalization and modernization as well as technological and societal change at play. And those forces very much affect the clans, and the evolving role of women as it plays out over the trilogy.

AMY: In Jade City and Jade War, Kekon is incredibly violent and your fight scenes are spectacular—which isn’t surprising given your black belts in both karate and kung fu. Further, the fighting in your world is deliberately designed to be close, hand-to-hand rather than with guns, which are of limited use due to Green Bone magic. And this style of fighting is tangled up with the Green Bone honor code, which includes phrases like “I offer you a clean blade” to invoke a duel, and the idea that some deaths are clean and others are not—but also includes aisho, a prohibition on a Green Bone attacking someone who doesn’t wear magical jade. Talk to me about your view of violence and honor codes.

FONDA: I’m fascinated by honor cultures, and I researched everything from the samurai code of bushido to the history of the code duello commonly adhered to in Europe and the southern U.S. Then I set about creating a fictional honor culture with strictures specifically designed for my fantasy world with magic martial arts powers. I love to write stories with explosive, gripping scenes of action and violence—but I’m also a stickler for immersive and believable worldbuilding. No society can survive constant arbitrary violence and out-of-control vendettas—there have to be rules that clearly stipulate when and how grievances are settled by violence. The idea, for example, that soldiers would not target women and children has been commonplace for most of military history; magically enhanced super warriors would have a similar prohibition against targeting those without jade. Duels are meant to contain feuds and prevent them from spiraling into further violence—hence the idea of a “clean blade” that would prohibit retaliation. In short, I’m satisfying both my desire for sociologically sound worldbuilding and kickass fight scenes!

AMY: Duty is a recurring theme in your work. In fact, you spoke to Lightspeed Magazine about something similar in 2018, the idea that your characters believe they have a choice, but ultimately, they do not. Shae’s journey, in particular, highlights this theme for me: She removed her jade and went to Espenia, only to return home in a time of crisis, resume wearing her jade, and assume a top-tier leadership position in her clan. Why is the idea of duty—or perhaps family—so important to your work?

FONDA: Throughout the Green Bone Saga, family is both a source of great strength and great personal conflict. The main characters go through a lot—but they do it together. So many fantasy stories in Western canon are based on the “hero’s journey”—the singular hero gradually leaving behind all that is important to him in order to triumph alone. It’s a very individualist mentality. I’m inspired by both Western and Eastern storytelling traditions and very much wanted to write a different kind of epic fantasy. I believe that my sensibilities of what’s important to me to portray in fiction are influenced by the fact that I’m a second generation Asian American; my parents were immigrants who struggled in a new country in order to give their children a better future, and they stayed together for years longer than they should have out of a sense of family duty and sacrifice.

This experience is far from culturally exclusive; family and duty are so important and entwined in so many people’s lives, and that constant tension between love and frustration, personal desire and obligation to others, independence and belonging are themes that make for deeply compelling and relatable human drama in any story, even one about magical gangsters.

AMY: You’ve wanted to be a writer since you were a kid—but your first career was as a corporate strategist before you came back to writing. You’ve written young adult (Cross Fire, Zeroboxer) and adult (the Green Bone Saga) works, and now you’re moving into comics, of which you’ve said, “In short, comics is a far more rapid, free-flowing, collaborative creative environment. That presents challenges as well as fantastic opportunities. There’s a sense of “we’re all making this up together as we go along” energy that is both mildly terrifying as well as very energizing and freeing, and it’s a nice counterpoint to the way I work on novels.” How do you approach risk, as a former corporate strategist, as a writer, and as a person?

FONDA: I tend to be an all-or-nothing sort of personality. When I decided to make a career switch into writing, I went for it almost obsessively and never looked back. At the same time, I’m a very pragmatic person, and I’m always planning ahead, always mulling possibilities and contingency plans. So I would say that I’m definitely a risk taker, but the sort of risk taker armed with a spreadsheet! I’m easily bored and always want to push myself and take on new challenges, but every step has to make sense to me, I have to feel like I’ve done my research. Sometimes, things don’t work out, or they don’t happen the way I planned, but that’s life, and you move on. When it comes to writing, I take the long view. This career is a risk, every project is a risk, but at the end of it all, I want to have a large body of quality work that I’m proud to look at on my shelf.

AMY: Sirens is about discussing and deconstructing both gender and fantasy literature. Would you please tell us about a woman or nonbinary person—a family member, a friend, a reader, an author, an editor, a character, anyone—who has changed your life?

FONDA: My high school English teacher, Ms. Carson, was one of the first real fans of my writing. She told me that I had a true gift for words, and she encouraged me to nurture my skills and to continue writing. And I sorely disappointed her! I’ll never forget the look on her face when she found out that I was going to study finance in college. “Finance?!” I could tell she believed that wasn’t my true calling, that I should follow my passion and talent. She was right, of course. I lost touch with Ms. Carson, but many years later, when I began writing seriously for publication, I would often think of her voice in my head and her supportive notes in the margins of my early work and take comfort knowing there was one person, at least, who’d believed I had what it took to be a writer.

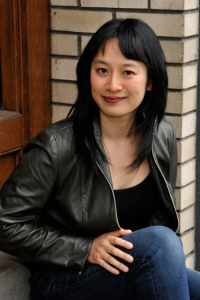

Fonda Lee writes science fiction and fantasy for adults and teens. She is the author of the Green Bone Saga, beginning with Jade City (Orbit), which won the 2018 World Fantasy Award for Best Novel, was nominated for the Nebula Award and the Locus Award, and was named a Best Book of 2017 by NPR, Barnes & Noble, Syfy Wire, and others. The second book in the Green Bone Saga, Jade War, released in 2019 to multiple starred reviews. Fonda’s young adult science fiction novels, Zeroboxer (Flux), Exo, and Cross Fire (Scholastic), have garnered accolades including being named Junior Library Guild Selection, Andre Norton Award finalist, Oregon Book Award finalist, Oregon Spirit Book Award winner, and YALSA Top Ten Quick Pick for Reluctant Young Adult Readers. In 2018, Fonda gained the distinction of winning the Aurora Award, Canada’s national science fiction and fantasy award, twice in the same year for Best Novel and Best Young Adult Novel. She co-writes the ongoing Sword Master & Shang-Chi comic book for Marvel. Fonda is a former corporate strategist who has worked for or advised a number of Fortune 500 companies. She holds black belts in karate and kung fu, loves action movies, and is an eggs Benedict enthusiast. Born and raised in Canada, she currently resides in Portland, Oregon.

For more information about Fonda, please visit her website or her Twitter.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter