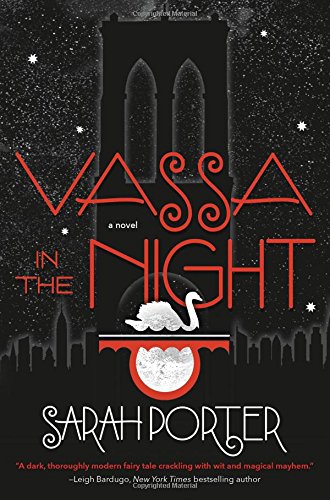

Read Along with Faye is back for the 2017 Sirens Reading Challenge! Each month, Sirens communications staff member Faye Bi will review and discuss a book on her journey to read the requisite 25 books to complete the challenge. Titles will consist of this year’s Sirens theme of women who work magic. Light spoilers ahead. We invite you to join us and read along!

On paper, Sarah Porter’s Vassa in the Night should be my cup of very strongly brewed Russian tea. I love reimagined fairy tales, learning about Russian folklore, and gorgeous prose. I especially love books set in cities, and Vassa in the Night starts and ends in the gritty, non-gentrified parts of Brooklyn that do not yet have overpriced cafes and clothing stores with distressed jeans. I would even say that I do weird fairly well—though this is level of weird is somewhere between Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s short stories and Sarah McCarry’s All Our Pretty Songs.

Porter’s novel begins with teenager Vassa, living in a Brooklyn apartment with two stepsisters Stephanie and Chelsea. She has a magical doll, Erg, who talks, demands to be fed, and protects Vassa at all costs. The nights have begun stretching longer and longer, and one night, Vassa comes home to all the light bulbs broken. Stephanie, the mean stepsister, manages to cajole/convince/manipulate Vassa into going to the most dangerous bodega of all time called BY’s to pick up some light bulbs. BY’s is a neighborhood death trap—people go in, get framed for stealing (with the aid of dismembered hands and other body parts sneakily dropping in goods in customers’ pockets) and then get literally beheaded with their heads propped up on a stake to discourage future thieving. Except BY’s is run by Babs Yagg, an incarnation of Baba Yaga, and all the cops look the other way because BY’s is located in a neighborhood where poor people live and no one could possibly care about, plus it keeps their numbers down.

Here’s where I find out that Vassa in the Night follows the Russian folktale “Vassilisa the Beautiful” fairly faithfully, which I did not know much about going in but read up on after the fact. Had I known that, would I have felt delight instead of confusion? Predictably, Babs tries to frame Vassa for stealing, but with the help of Erg and some magical bartering, Vassa agrees to work for Babs for three nights in the store. The magic that follows is deftly updated for a modern retelling, with Vassa learning more about Babs’s past as well as her own, as well as how to win her freedom (and the freedom of other imprisoned entities).

Vassa in the Night is dark and poetic, and Porter doesn’t shy away from ruthless, gruesome detail. The scenes in which Erg is choked up within flesh, or the very thorough hacking and dismemberment of one of Vassa’s classmates, can’t be understated. Porter went there and did so fearlessly. At the same time, there are passages of such beauty and clarity, like when Babs scolds Vassa for using moral terms like “good” and “right” versus “bad” and “wrong,” and the physical manifestation of Erg as a metaphor for Vassa’s loneliness is simply breathtaking.

But yet, there was something I wasn’t getting. Despite being set in a non-gentrified neighborhood, I wasn’t able to detect much immigrant mentality or class struggle anywhere in the text, though someone with more experience reading Russian literature could speak more to this. The dream sequences were confusing, the stakes were high, and with the exception of one scene with Vassa’s classmates trying to “game” the store, the characters didn’t speak strongly to me. It’s hard for me to describe Vassa or Babs—both felt like fairy tale characters in the abstract, as did Tomin (categorically good) or Stephanie (evil enough to want to send her step-sister to near certain death). I almost wish we spent a little bit of time with Vassa at school, so those relationships could crystalize, or at home with her stepmother Ilissa, though Stephanie and Chelsea do get more airtime. The bulk of the book is Vassa in the store. It feels weird to admit this, but the character I felt most connected to was Dexter, the dismembered hand, who does Babs’s dirty work but later repents for it.

With that said, the ending of Vassa in the Night is delightfully subversive, with Vassa reuniting with the only family member who cares about her—her stepsister Chelsea! I wish we got more of the Vassa-Chelsea relationship, since how many fairy tale retellings have you read about stepsisters who get along?

Faye Bi is a book-publishing professional based in New York City, and leads the Sirens communications team. She’s yet to read an immigrant story she hasn’t cried over, and is happiest planning nerdy parties, capping off a long run with brunch, and cycling along the East River.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter