Not being able to gather in person with the Sirens community in 2020 was heart-rending. But it also gave us the gift of time: a chance, after more than a decade of work, to take a breath and consider what Sirens is today—and what we want it to be tomorrow.

Sirens is a conference that actively seeks to amplify voices that are pushing boundaries in speculative spaces—and specifically, are pushing those boundaries in the direction of a more inclusive, more empathetic, more just world. Since we featured works on this year’s villainous theme last year, this year’s Sirens Reading Challenge instead showcases 50 works by female, nonbinary, and trans authors that envision that better world—and we’re exploring what that means to us in a series of six posts, using those works as reference points.

Our first two posts discussed finding and sharing those speculative and nonfiction works that, respectively, reclaim what it means for us to be from somewhere and transgress boundaries, expectations, and limitations for all people of marginalized genders. Today, we discuss revolution and the collective action we need to transform our quotidian skirmishes into a new and better world.

Revolution

We wake up every day and go to war.

And our battles are fought at all times, on all fronts, with little succor or relief. We battle partners who race to work while we scramble, last night’s dishes still in the sink and the plumber on the way, before finally tackling our own day. We battle wolf-whistles on the street, groping in the subway, and snide comments about our gender presentation, everyone telling us to “smile” like we should be grateful for any kind of attention, no matter its intrusion or danger. We battle mediocre white, cisgender male bosses, who pay us less and promote us less and sideline us because we are too assertive, too passive, too emotional, too sure of ourselves, too focused on our families. We battle female thought-leaders—rich, white-woman beneficiaries of tokenism—who encourage us to lean in or proclaim that, if we just tried harder, we could have it all. We battle cisgender non-white men in our own communities, a result of extremist interpretations of religious teachings or a consequence of colonialism. We battle the empty fridge, the overflowing laundry basket, the unfinished work project, all perceived failures of our past selves.

But those are just the skirmishes, the quotidian clashes that we’ve largely learned to shrug off or ignore, the daily indignities of being a person of a marginalized gender, especially for those of us with multiple axes of oppression. The constant conflict that is meant to distract us, to exhaust us, so that we aren’t focused on the larger war: the one against our white heteropatriarchy-designed society, with its demands and limitations and lies. The rotten systemic mores that are designed specifically to create and maintain power for only white, cisgender men—who make up less than 30% of America—and those who enable them.

We wake up every day and go to war. We fight our own battles, alone. We reclaim and transgress until we are exhausted. We assert our truths and our needs and ourselves, until we feel like our bodies are, themselves, a battlefield. Every day, the war comes to us, and every day, we fight it.

But we can do only so much alone. We need collective action. We need foundational change. We need a revolution.

We need an unequivocal rejection of the societal structures that have been built by the white heteropatriarchy, by colonizers, by capitalism. We need an essential reimagining of irredeemably biased systems. A full-throated commitment to valuing our reclamations, our transgressions, and ourselves, not just when convenient, but every day and in every way. A determined bending of the universe toward justice.

And so, in the speculative space that is Sirens, our third mission statement is revolution: to find and share those stories that revolutionize how we see our society, our structures and systems, and our place within them. That make us see things about our world more clearly—and show us how change might be possible. That ink blueprints for reshaped, reimagined worlds. Even more so, that create worlds devoid of the battles we must fight in our own. Worlds where we are accepted for who we are, who we love, who we want to be. Worlds where people of all genders are already fundamentally human, and can grapple with new issues, new concerns, new truths. Worlds that are revolutionary.

Because we need a revolution. We need a thousand revolutions.

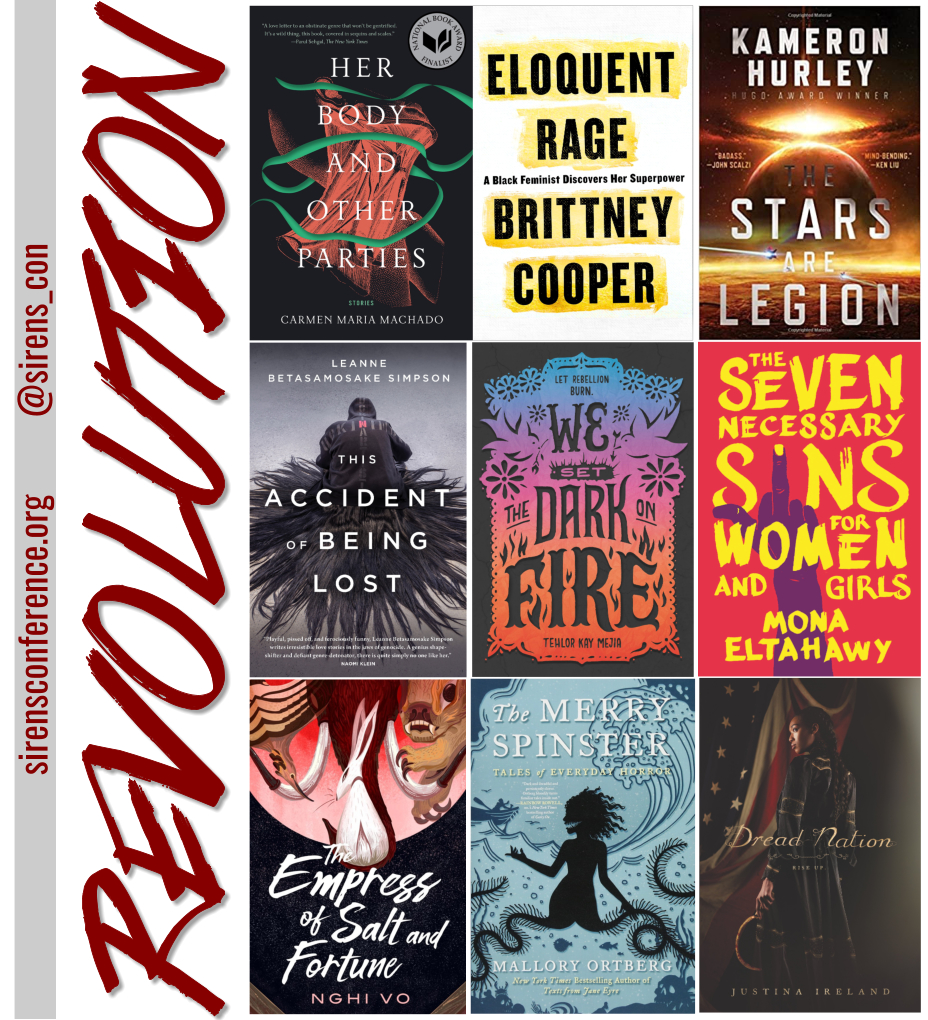

Revolution Works

The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls—queer, Egyptian-American feminist Mona Eltahawy’s fuck-you feminist anthem—exhorts women and girls around the world to deliberately, uncompromisingly practice seven “sins” forbidden them by the patriarchy: anger, ambition, profanity, violence, attention seeking, lust, and power. Through a combination of searing academic work and lived experience as an activist around the world, Eltahawy argues for a singularly blazing, deliberately profane approach to feminist thought, one that demands that patriarchy fear the power of transgressive feminists to defy, disrupt, and destroy it. Eltahawy’s work, centering queer, BIPOC feminism, is a raised fist, a relentless repudiation, an inexorable revolution.

Brittney Cooper’s luminous, fearless brilliance is on undeniable display in Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower. In this collection of essays, Cooper interrogates—consummately, furiously, hilariously—the warring messages of feminism for Black women. But Cooper’s work is more than a refusal to allow mainstream feminism to elide Black women, or even a rage-driven conflagration, though it is certainly both: She also addresses Black women with extraordinary compassion, holding their sorrow and pain gently, nurturing their friendships, their love, and their selves. Her revolution is driven by equal parts anger and kindness. And she sees the world as it is, and as it could be, as clear as day.

Carmen Maria Machado’s ferocious, genre-bending collection, Her Body and Other Parties, is a series of feminist issues incarnate. Unlike Eltahawy’s and Cooper’s works, Machado’s medium is fiction, made all the more honest for its invented stories. Starting with “The Husband Stitch”—a virtuoso retelling of the Velvet Ribbon fairy tale as a fabulist, modern tale of privacy and the inevitability of male intrusions—Machado incisively lays bare the constant oppressions and all-too-familiar compromises of women’s shared experiences. Revolution can come only after fully realizing the rapacious horror of our quotidian lives—a gift that Machado provides.

Speaking of quotidian horrors, The Merry Spinster: Tales of Everyday Horror, by Mallory Ortberg (now Daniel M. Lavery), uses familiar tales—fairy tales, folklore, children’s classics—to unearth unavoidable truths. Here is someone who understands the original, cautionary nature of our stories and how those stories travel societies changed, not to mention the everyday horrors of societal expectations, biased systems, and expected gender performance, rendered all the more apparent for their quasi-familiar, fantastic settings. Lavery detonates all of that in his revolutionary short story collection, sometimes slyly, sometimes heart-shatteringly, always with tremendous humanity.

A clarion cry for the world to better treasure humanity, and for humanity to better treasure the world, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s This Accident of Being Lost, a genre-breaking, ground-breaking collection of stories and songs, is wildly experimental and deliberately incendiary. An award-winning Nishnaabeg storyteller, not to mention provocateur and poet, Simpson incisively analyzes and condemns colonialism in her work, often in surprising ways. (Have you ever guerilla-tapped maples in a residential neighborhood? Or considered that Lake Ontario may want to flood the world and remake it?) Simpson’s work is invariably smart and often demanding, requiring that readers consider the world differently than before, through rage, through despair, through sorrow, through joy.

Kameron Hurley’s work always insists on revolution, an explicit rejection of hypermasculine nihilism combined with a purposeful centering of radical, communal kindness. The Stars Are Legion is her battle cry for that revolution, a work that eschews male characters entirely in its unremitting exploration of reproductive justice. Hurley centers two unreliable narrators in her space opera: one with amnesia, the other a known liar. As the former makes her very squishy way through a living spaceship, and the latter plays a game of queens and pawns, Hurley weaves science fiction with body horror to explore—fiercely, powerfully—a world of women’s issues.

Justina Ireland is undeniably dazzling at power deconstructions, especially when she’s interrogating the history of race in America—and Dread Nation is all that wrapped up in a bravura horror novel. In the aftermath of the United States Civil War, the dead have risen as zombies, and Black and brown girls are pressed into combat schools in order to develop the skills necessary to protect the more genteel members of society. As Jane navigates this new reality, Ireland cleverly constructs an America both outrageously different from, but with all-too-familiar reflections of our own: one that tells the terrible truth of oppression, marginalization, and humanity in America.

Tehlor Kay Mejia dismantles power structures as well in We Set the Dark on Fire, her shining, subversive young-adult novel. In a Latinx world with shades of The Handmaid’s Tale gender dystopia, young women are trained at the Medio School for Girls for one of two roles: to manage a husband’s household or to raise his children. While both options offer privilege—comfort, security, luxury, freedom from the turmoil of the lower classes—top student Dani, recruited as a spy by those who wish for a more equal, more just society, wants something bigger, including a forbidden love. Mejia’s incisive, riotous feminism imbues her propulsive tale of rebellion, revolution, and finding yourself.

When we contemplate speculative revolution, an indictment of monarchy is required—and Nghi Vo somehow stuffs an epic’s worth of high-fantasy political intrigue into her novella, Empress of Salt and Fortune. Told in retrospect by Rabbit, a handmaiden sold for five baskets of dye, Vo’s slim work chronicles the story of In-yo, a woman from the north sent south as a trophy of war for a political marriage, and how she—alone, hated, in virtual exile—crafts her vengeance. Incandescent, gorgeous, dangerous, with Vo’s trademark carefully wrought prose, The Empress of Salt and Fortune is a revolution, one where even marginalized people can bring history to heel.

This post is the second of a six-part series on Sirens’s mission. You can find the first two posts here: reclamation and transgression. We will update this post with links when all posts are published.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter