Each month, Sirens co-chair Amy Tenbrink reviews new-to-her fantasy books by women and nonbinary authors—and occasionally invites other members of the Sirens community to do so. You can find all of these reviews at the Sirens Goodreads Group. We hope you’ll read along and discuss!

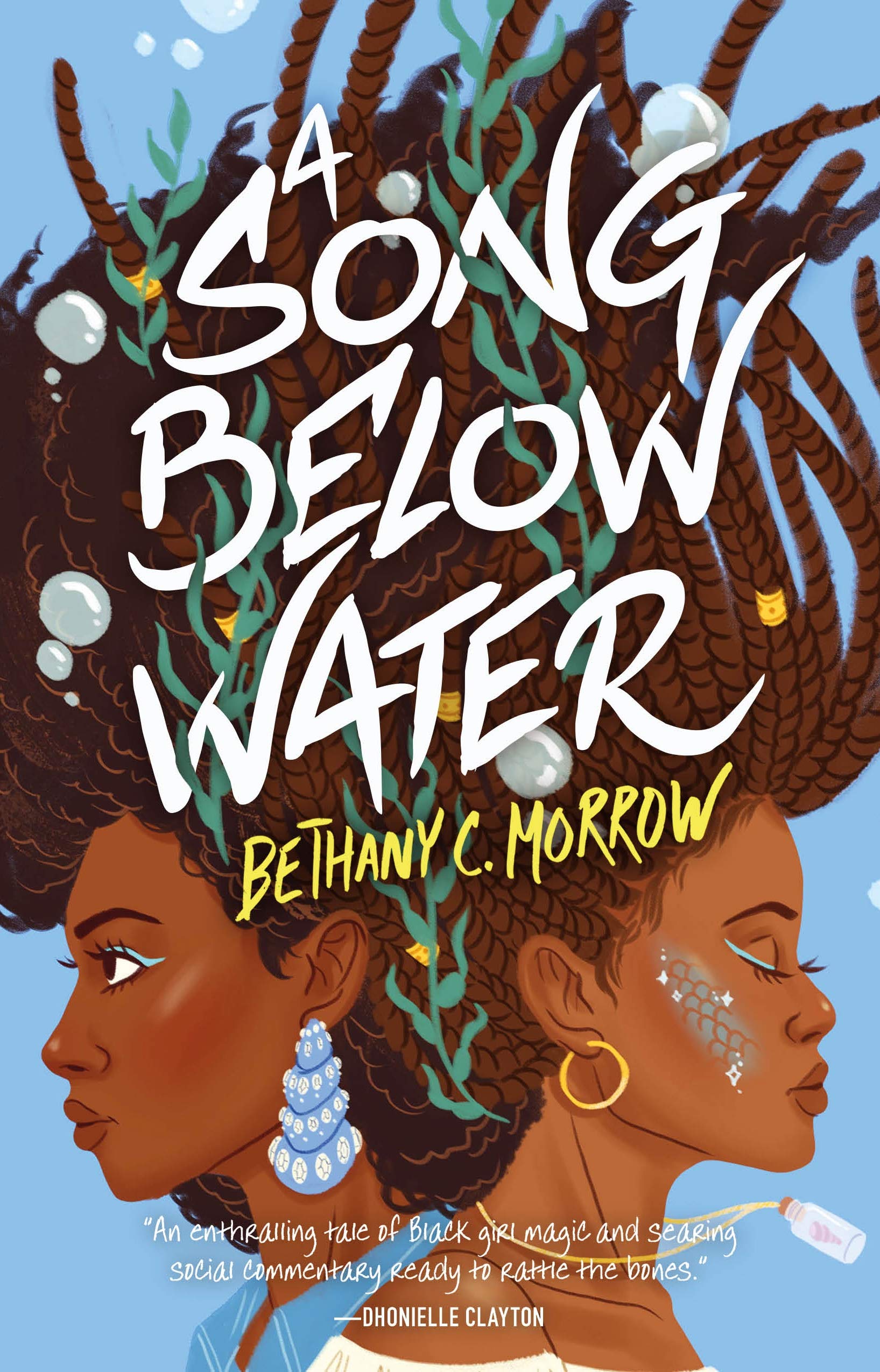

This month, Faye Bi reviews Bethany C. Morrow’s A Song Below Water!

To my fellow Sirens,

It’s not a surprise to any of you that I claim the act of reading as revolutionary.

We know that reading is more than literacy and comprehension. We know that it’s about stories. Who tells them, who gets paid to tell them, and who can make a living off telling them. Whose books get more promotional budget online and off, whose books get placed front and center at bookstores and libraries, whose books get taught in schools instead of being outside reading, and whose books get revered as “great literature.” This discussion is not new to us. But you might be wondering, what can I do? I can’t singlehandedly force all these institutions and corporations to reckon with their racist, sexist, colonialist pasts.

But there is a lot we can do. So much we can do. While I am furious and dismayed on a daily basis, I control one realm entirely: Me. What I choose to read. What I choose to review. What I choose to recommend. What books I choose to buy and where I choose to buy them. And I know—like I hope you all do—that reading critically is an act of resistance.

And so, I am reviewing Bethany C. Morrow’s A Song Below Water for you, Sirens community. And I am reviewing it here, for Sirens, where I am not limited by wordcount or editing or pearl-clutching, and I can tell you exactly what I think.

A Song Below Water is set in Portland, featuring two Black teenage girls: Tavia, who is a siren, a group of magical people maligned for its association with Black women; and Effie, who plays Euphemia the Mer in the local Ren Faire and has a mysterious skin condition that is somehow linked to her childhood trauma. Effie currently lives with Tavia and her parents, and so the two are sisters, supporting and looking out for each other as they navigate family, school, life, secrets, and literal Black girl magic to save themselves.

To begin, Tavia’s siren identity is an elegant metaphor for being one of the most vulnerable in society. The book opens with a girl murdered by her boyfriend, and because of that girl’s suspected siren identity, her boyfriend will likely be acquitted. Because sirens are only Black women (but not all Black women are sirens), they are perceived as dangerous—and if you recall your lore, a siren’s voice can lure people into doing things against their will. That means sirens have incredible power, but because people fear Black women, sirens’ voices are literally stifled and silenced. There’s that girl on the reality show, for instance, who voluntarily uses a siren collar—designed to silence her voice and her power—to make others “feel safe” around her, and another Black girl, Naema, who wears one as a joke.

But can you imagine using a siren voice as a Black teenaged girl, when, say, the police pull you over?

Effie has her own grief to grapple with. She’s human as far as she knows despite her shedding skin, but she grew up without a father, and her only connection to her mother is that they both played mermaids at the local Ren Faire. Not only must she deal with the large gargoyle keeping watch over her and her grandparents’ continuing to keep family secrets from her, she’s known in the community as “Park Girl”—due to being the sole survivor of a mysterious attack when she was nine where all the other children were turned to stone. Now these “statues” are practically an attraction in a weird Portland tourist campaign, which underscores in a twisted way the variety of methods Black bodies are used for entertainment and how others trivialize her pain.

Morrow’s social critique is devastating, for all the reasons I detail above, but also because she lays out the emotional harm done by “well-meaning” allies, who are white, other races, and other magical identities.

An interesting foil for people of color or other marginalized groups is elokos—dwarf-like creatures who ring charismatic bells to lure human prey and then eat them. In Morrow’s world, elokos are a more socially accepted class of magical being, to the point that they hold political power, especially in Portland, which has attracted a significant eloko population because of that power. Tavia dates Priam, an eloko boy, before the start of the book, and in the best face-palming passage, she recounts the moment they broke up: when Priam bit her neck while kissing, and Tavia launched into an in-depth explanation on why that didn’t bother her despite eloko mythology. But on a more serious note, there are examples of Tavia and Effie at a police brutality protest with other honor students (of course, chaperoned by white parents!) that made me shiver and weep, and I could write an entire essay about Naema, another Black girl and also an eloko, who illustrates the trap of the model minority myth. Naema is especially fascinating as she is one of few outright villains on the page.

But besides pain and critique, there’s joy. Black joy. Tavia and Effie’s sister bond is strong and wonderful to read, and they are each other’s refuge when everyone else around them has failed them. Repeatedly. Not just allies, but also their families, other Black girls, and Black men. There’s a lovely scene at the climax of the book, where the two of them are in a mystical forest setting with lives on the line and literal chaos happening around them, and what do they do? Have a heart-to-heart about their emotional wellbeing.

Morrow brilliantly uses this mythos of sirens, gargoyles, elokos, sprites, mermaids, and magic to examine what it’s like to be a Black girl in America.

And with it, she seamlessly and ambitiously unpacks intersectionality, racism, sexism, police brutality, protesting, affirmative action, gentrification, education, beauty standards, and more. She calls out people who admire and consume Black culture but don’t see the pain of Black creators, and those who call themselves “woke” but are horrified and immobilized when their eyes are opened. I found the density of revelations to be necessarily challenging—and that effort allowed me to appreciate the skill involved in the telling. You know already that this book isn’t newly relevant in the summer of 2020, and that the protests, the pain, the violence, and the disenfranchisement of Black bodies and Black livelihood has been going on for a long, long time.

Tavia and Effie work together to save themselves because they have to. No one will do it for them. If you see parallels to Morrow’s sirens in your real life, I see your pain. I see it and am horrified, but I will do everything in my power so your voice can be heard, because you live these horrors daily. If you, like me, are not a Black girl, A Song Below Water is a call to action. There’s so much to do. Wherever you are on your journey to antiracism, this book is a part of it.

Let’s get to work.

Faye Bi is the director of publicity at Bloomsbury Children’s Books, and spends the rest of her time reading, cycling, pondering her next meal, and being part of the Sirens communications team. She’s yet to read an immigrant story she hasn’t cried over, and is equally happy in walkable cities and sprawling natural vistas. You can follow her on Twitter @faye_bi.

Faye Bi is the director of publicity at Bloomsbury Children’s Books, and spends the rest of her time reading, cycling, pondering her next meal, and being part of the Sirens communications team. She’s yet to read an immigrant story she hasn’t cried over, and is equally happy in walkable cities and sprawling natural vistas. You can follow her on Twitter @faye_bi.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter