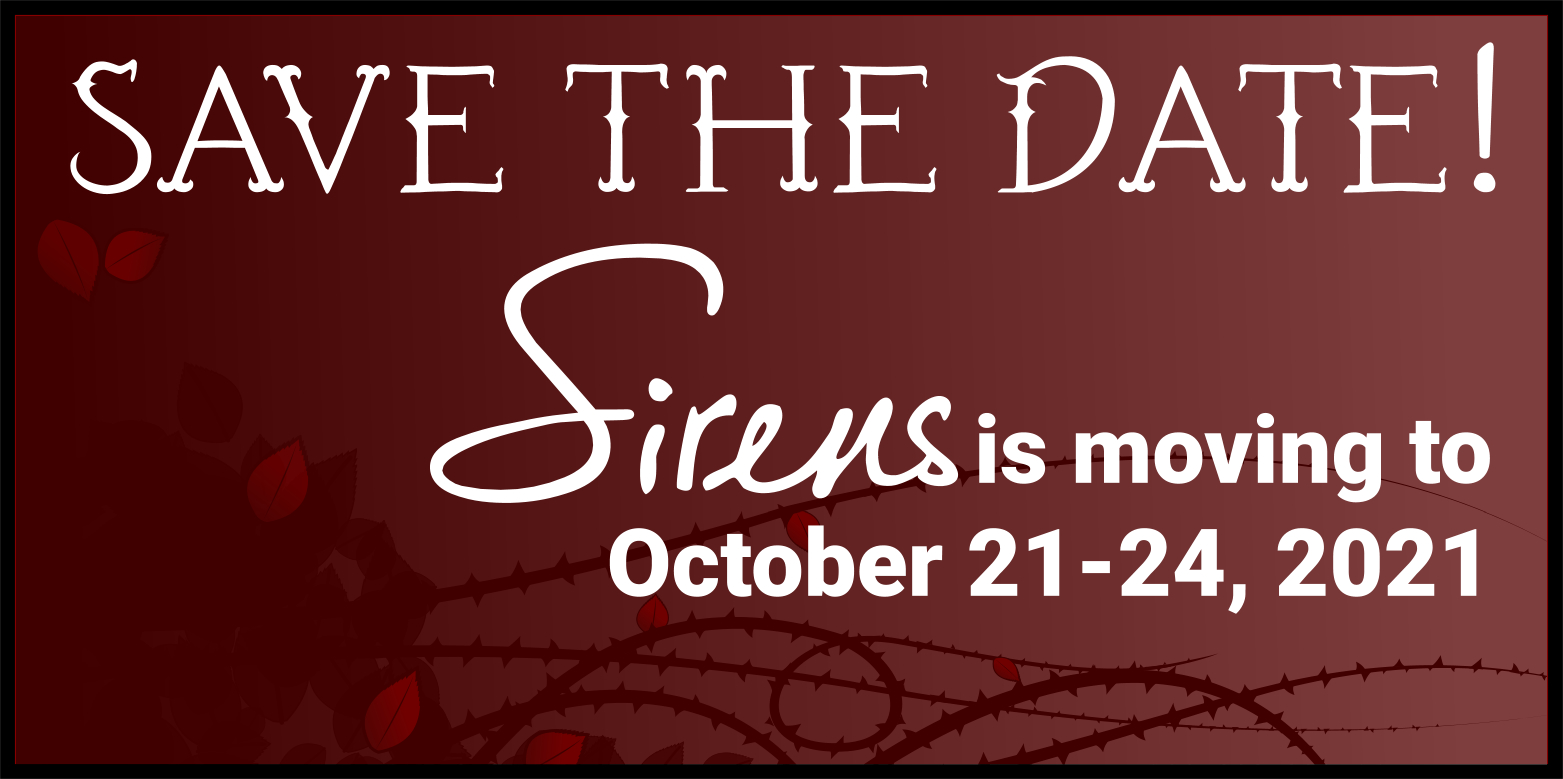

At Sirens, attendees examine fantasy and other speculative literature through an intersectional feminist lens—and celebrate the remarkable work of women and nonbinary people in this space. And each year, Sirens attendees present dozens of hours of programming related to gender and fantasy literature. Those presenters include readers, authors, scholars, librarians, educators, and publishing professionals—and the range of perspectives they offer and topics they address are equally broad, from reader-driven literary analyses to academic research, classroom lesson plans to craft workshops.

Sirens also offers an online essay series to both showcase the brilliance of our community and give those considering attending a look at the sorts of topics, perspectives, and work that they are likely to encounter at Sirens. These essays may be adaptations from previous Sirens presentations, the foundation for future Sirens presentations, or something else altogether. We invite you to take a few moments to read these works—and perhaps engage with gender and fantasy literature in a way you haven’t before.

Today, we welcome an essay from Meg Belviso!

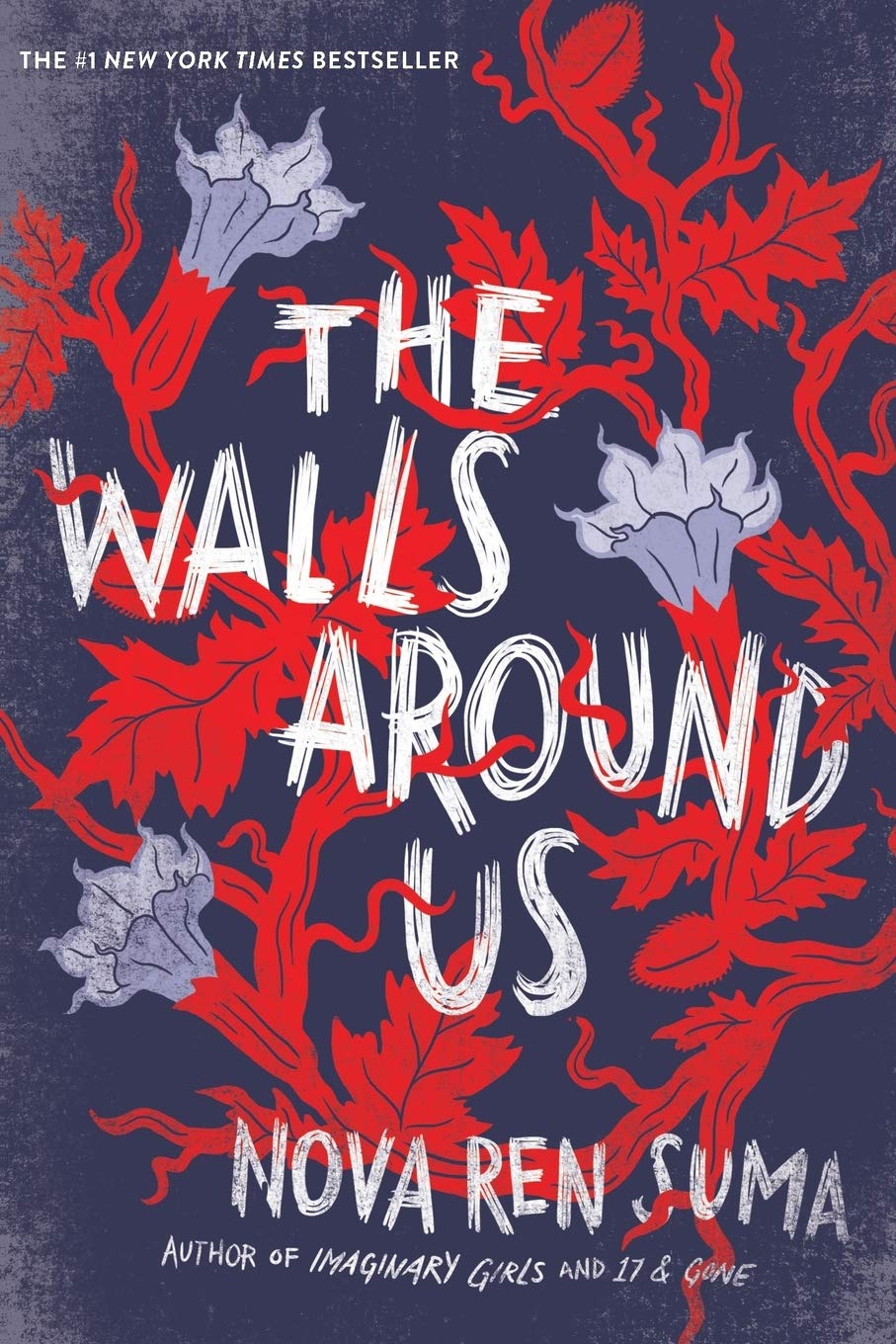

A Room of Her Own: The Post-Modern Haunted Houses of Nova Ren Suma

by Meg Belviso

There’s something enduring about a haunted house. For centuries, it’s called up images like the Gothic family manse crumbling from the inside, passed from one heir to the next, or the duplex on the corner where families come and go a little too fast. The whole idea of a house suggests a place to put down roots, settle down, grow up, over and over through many generations. For centuries—from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Ann Radcliffe to Emily Brontë to Barbara Michaels—when we talked about a haunted house, we meant a place where remnants of the building’s past affected the people of its present, threatening or influencing their future.

So goes the traditional haunted house story.

Modern horror, however, has begun to focus more on the haunted house as a transitional space. That is, a dwelling without a fixed position in time. A decaying building, for instance, that no longer functions in its original capacity, but has not yet become a ruin with a fixed place in the historical or mythical past. A Roman Colosseum that has lost its meaning as a working arena, but not yet found its meaning as evidence of an ancient empire.

Sometimes the modern ghost story emphasizes this idea further by giving the space other “in-between” qualities as well. The mansion in Alejandro Fernando Amenábar Cantos’ 2001 film The Others takes place on the Isle of Jersey, a self-governing possession of the British crown off the coast of France, in 1945, a time between WWII and what we’ve come to recognize as the post-war period. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s House of Seven Gables has a firm historical and legal history. By contrast, Amenábar has intentionally set his story in a place that does not belong to WWII, the post-war period, Great Britain, or France, but lives in a transitional space at the center of all of them.

In The Uncanny Child in Transnational Cinema, Jessica Balanzategui links this shift to twenty-first century anxiety about an increasingly uncertain future and a feeling that the foundations of society that had once seemed solid are now vulnerable. Today’s young—and even not that young—adults, for instance, are often accused of immaturity when they fail to hit landmarks by which life was measured in the past. One of the most obvious examples of this is home ownership.

These accusations of personal irresponsibility often flat-out deny the financial instability faced by so many young adults who, unable to follow the path their grandparents did, threaten critics by not only choosing to forge their own path, but questioning the value of paths in general.

The children at the center of postmodern stories are often young people who “will never fulfill futurity’s promise of becoming an adult…but instead linger at a point of continual transition to a corpse, dust, a ghost, a memory.” The settings of modern haunted house movies reflect this “unsettlingly liminal space of transition between states, with no triumphant end state.” Not becoming adults, but simply becoming.

Adolescence, that period of life between childhood and adulthood that’s center to YA lit and its intended audience, is also a transitional space. Today’s YA audience has grown up in the twenty-first century. Most YA heroes, like fictional heroes in general, exist firmly within fixed, linear time. They are no longer the children they were and not yet the adults they will be. Even in the bleakest circumstances, they move towards the future, figuring out what kind of people they are going to be, what values they will live by, how they will change the world. Sometimes they’re motivated by the fear of growing into the wrong kind of adult—of selling out, giving up on their dreams, perpetuating the unjust system they live in now. But even then, and even if they develop into what we would call a villain, they will be part of the future. They’re making choices, developing, moving forward.

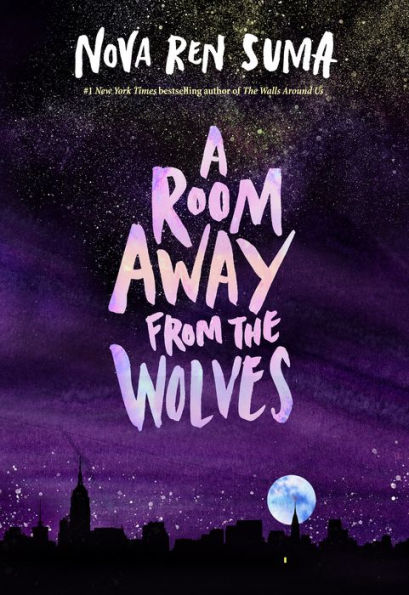

In her two post-modern haunted house books, The Walls Around Us and A Room Away from the Wolves, author Nova Ren Suma connects these two transitional spaces, the haunted house and the adolescent. In doing so, she creates a new—one might even say revolutionary—bildungsroman for the twenty-first century.

Suma’s haunted spaces are not traditional homes, but temporary housing populated not by families but inmates and tenants. Specifically, young women between childhood and adulthood. They are places to reflect on the past and prepare for the future before aging out and moving on, rejoining the normal progression of life.

In The Walls Around Us, Amber Smith and Orianna Speerling are sentenced to do time at the Aurora Hills Secure Juvenile Detention Center. When she reaches eighteen, a prisoner is sent either to a jail for adults to finish her sentence or released. Either way, according to Amber, she ceases to exist in the world of Aurora Hills, not just physically, but in the memories of the other inmates. “We’d recite [a former inmate’s] stories until the names and specific characteristics faded away…until it was somegirl, which may as well have been any of us.” When Amber glimpses a spectral girl in the prison who doesn’t belong, she’s not the ghost of a girl who once served time in the prison, but a vision of a girl who has not yet arrived. The inmates regret the past and acknowledge no future. There is only now.

Bina Tremper, the heroine of A Room Away From the Wolves, also checks into a temporary place. In this case, an old-fashioned boarding house that doesn’t seem to belong in modern Manhattan. At first Bina worries that she won’t be able to pay for more than one month at Catherine House, but she soon realizes that she’s no more able to leave it than the inmates of Aurora Hills can walk out of their prison. The staircase walls are lined with decades of annual photographs of former Catherine House residents, but the young adult lodgers themselves don’t seem firmly attached to any single time period at all. Bina herself carries bruises that still look fresh weeks later, as if no time has passed. Although her mother left New York decades earlier, Bina finds her belongings in her room. The house, too, seems to exist in a state of suspended decay, shabby and threadbare, but still habitable for now.

Where many YA stories take place in environments that explicitly measure physical development and count the passage of days, months and years, such as schools or camps divided by age, Aurora Hills and Catherine House have both, in their own ways, extracted themselves from the normal progress of time.

Suma’s girls are physically trapped by their surroundings, yes, but they also fear leaving them.

Both Amber and Bina begin their narratives watching another girl attempt a desperate and potentially deadly escape. They watch and choose not to follow. Amber admits, “No matter how I may have pictured myself leaving this place—face-first or feet-first—truth is, I can’t leave it. I would never. That’s my real secret.”

When told she’s being released from the prison, Amber’s attitude is similarly reluctant: “[The guard] was walking me down the corridor, confused maybe as to why I wasn’t leaping around for joy….We passed the window…and the blue sky flashed, and I turned my face away.” No matter how much she hates the prison, the outside world has betrayed Amber too much for her to want to return to it. She no longer trusts that she can restart the process that was cut short when she was convicted.

To emphasize this point, Suma creates a villain who moves in only one direction, forward, like a shark. Vee can’t wait to leave behind her hometown, her boyfriend, even her best friend, to reach the future she’s planned for herself since she was eight. Her best friend Ori, by contrast, voluntarily postpones her own pointe training to wait for Vee to catch up and is said, by Amber, to live in fear of “the halfway mark of anything.” That hesitation costs Ori dearly when Vee’s plans are threatened.

Wolves’ heroine, Bina Tremper, has her own reasons to fear the future. She’s been raised on her mother’s stories of the summer she spent in New York. The summer she paid for a room of her own, went on auditions, collected postcards, was cast in a short film. The summer that came to an end when she returned to her abusive boyfriend and got pregnant with Bina. Over and over, it seems to Bina, her mother plans an escape, only to wind up once again in a life that isn’t her own. Over and over she entices Bina with optimistic plans, only to betray them.

That one summer in New York becomes, to Bina, the only time her mother really had a life at all. When her mother kicks Bina out of their house for a month, she understandably decides to run there herself.

Bina’s initial escape masquerades as forward movement—she vows to succeed at the New York life that her mother gave up by returning to her boyfriend, to live the future her mother didn’t. But once she’s in Catherine House, her life does not move forward at all. Where the traditional bildungsroman would focus on Bina making friends, finding romance and getting her first job, Suma’s story barely touches on these things. The people in Bina’s new world are too hazy and mercurial to be actual friends. Her search for a job consists of walking the entire length of Manhattan for days without result and without seeing or doing anything worth noting. Her actual experiences are more focused on trying to understand her present than to build any future. “Some girls wanted to leave Catherine House,” Bina says, “and I couldn’t fathom why…it felt like nothing bad could happen within these walls, beneath this roof, to me.”

Following in her mother’s footsteps and completing the journey her mother started was an excuse for running to Catherine House. But her mother’s dreams were never Bina’s. She didn’t want to be an actress. She was never really running toward an imagined future. She just wasn’t wanted enough in her present. When her relationship with her bullying stepsisters got too bad, her mother chose to send Bina away to keep the peace. Amber’s mother, likewise, doesn’t write or visit while Amber is locked up and won’t receive her phone calls. Amber knows without a doubt that her mother loved her husband—Amber’s abusive stepfather—more than her. Bina wonders if her own inconvenient birth was what ruined her mother’s life.

Neither Amber nor Bina is interested in fighting for a place in the world they left behind.

They’ve internalized the things they’ve been implicitly told about themselves: That Amber is guilty. That Bina interferes with the life her mother wants. Neither girl is freed from these notions in death. Rather, she accepts them. She embraces her life outside society and once she’s done so, she finds power and space she couldn’t see before. It’s not paradise, but it’s no worse than the life she left. At the very least, it’s not a world she’s allowed into only if she meets the demands of others, or accepts being loved less than anyone else. In these new worlds there are no guards, punishments or rules at Aurora Hills, no curfew or contracts at Catherine House. Like the founder of Catherine House herself, Amber and Bina jump off a roof to escape a trap and fly.

Amber and Bina aren’t figuring out who they are going to be or preparing to take their place in society. They are coming to understand what they are now, learning to navigate the spaces they have both chosen and had chosen for them, spaces outside linear progress and the world that failed to protect them. Not growing up, but becoming. They are not traditional ghosts, tied to a specific historical moment or event, but post-modern spirits that have opted out of the historical narrative entirely. They are a past that can’t be changed and a future that will no longer be.

But they are still here.

Meg Belviso holds a BA in English from Smith College and an MFA from Columbia University. During the week, she chronicles angel encounters as Staff Editor of the bi-monthly magazine Angels on Earth and she loves a good haunted house story. As a freelancer, she has written for many different properties, including several biographies in Penguin’s “Who Was…?” series.

Meg Belviso holds a BA in English from Smith College and an MFA from Columbia University. During the week, she chronicles angel encounters as Staff Editor of the bi-monthly magazine Angels on Earth and she loves a good haunted house story. As a freelancer, she has written for many different properties, including several biographies in Penguin’s “Who Was…?” series.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter