I used to think that, as people got older, they became more fearful.

When I was a small child, I feared nothing. Then I accidentally chopped a snake in half with a trowel. Then I feared snakes.

Then, during my first semester of college, the woman next door accidentally set her dorm room and mine on fire while we were both in them. Then I feared snakes and fire.

Then I got out of law school and discovered that the perfectionism demanded of women is not the golden ticket to wealth and success. Then I feared snakes, fire, and failure.

But I think, as humans, we tend to focus on what we fear, not things we no longer fear. Surely, there were a thousand things I feared as a child, as a teen, as a twentysomething: gross bugs, roller coasters, my parents’ divorce, public speaking, college, job searching, being fired, intruders, negotiating, whatever. But unlike snakes, fire, and failure, none of those fears have persisted. Every day, the vast unknown that gives rise to so many fears becomes just a little bit less. Every day, I rely just a little bit more on my own resourcefulness. Every day, I’m seemingly a little bit less likely to add a fourth fear to that unholy triumvirate.

So now I think that, as people get older, they become less fearful.

And correspondingly, I think that kids are afraid of damn near everything.

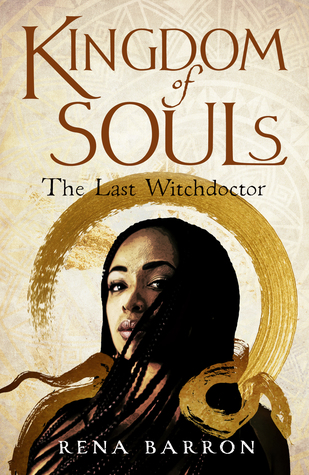

Which brings me to Kingdom of Souls by Rena Barron. If you were to read the flap copy of this book, you would expect a rather formulaic hero’s journey of a young adult book, albeit with a spectacular fantasy Africa setting. The flap copy rather unimaginatively focuses on the fact that Arrah, daughter of powerful witchdoctors, somehow has no magic. But to save the children of the kingdom, she needs to acquire some magic, and soon. And to do that, she needs to do the unthinkable: trade some of her lifespan for spells.

This is all very boring. Again, except for that magnificent fantasy Africa setting, you have all read that book before. I would call it Harry Potter-esque, but we all know that this trope goes back much further than that. So let’s ignore that supremely unhelpful flap copy.

Kingdom of Souls is about fear.

The first act does, indeed, focus on Arrah’s lack of magic: her disappointment in not having it, but more importantly, her perceived failure and her resulting otherness. Her fear of being different, of being less, of not living up to expectations. Her fear of disappointing her powerful parents and tribal chief grandmother. Her fear of what her friend-maybe-boyfriend, son of the Vizier, will think. Like teens the world over, Arrah has found her people: the only other two people her age who should have magic and don’t. But also like teens the world over, being part of a group of three outcasts isn’t so much better than being a sole outcast. Even if you’re the daughter of the Ka-Priestess making eyes at the Vizier’s son.

What galvanizes Arrah is what galvanizes so many heroines: harm to someone else. Children of the kingdom are disappearing and Arrah is determined to save them. To do that, she finds a way to acquire magic by sacrificing some of her lifespan—and with that she stumbles into the proverbial hornet’s nest. Arrah’s mother has been stealing the children in order to raise a powerful demon, so that that demon can impregnate her and she can give birth to a half-demon baby, who will in turn have the power to raise the Demon King, who was imprisoned by the orishas generations ago.

Whew. Frankly, if I lived in Arrah’s world, I would have four fears: snakes, fire, failure, and half-demon baby sisters.

The second act of Kingdom of Souls explores Arrah’s paralysis in the face of her multiplying fears. Her mother has magically chained both Arrah and her father; her family has been exiled to a land of demon energy; and Efiyah, her baby sister, is about to destroy the world. It’s a lot.

In the third act, though, Arrah masters her fears. She doesn’t eradicate them: They stay with her, a constant companion, as her sister wreaks havoc. But Arrah knows what she must do, despite her fears, and she just gets on with doing it.

So if you’re into a book where the heroine is afraid of the approximately 8,000 things that she should absolutely be afraid of, and she acknowledges those fears and saves the world anyway, have I got a book for you.

Unfortunately, aside from that angle—and again, Barron’s superb fantasy Africa setting—this is the sort of heroine’s journey book you’ve read a thousand times before. An unassuming, magic-less girl, of whom no one expects great things, is tasked with saving the world. There are adventures, there are gods, there’s some kissing, and the world gets saved. At least sort of; there’s a setup for a sequel.

And in the end, the biggest issue I had with Kingdom of Souls wasn’t the rather formulaic reluctant heroine’s journey—even though the reluctant heroine is a particular frustration of mine—but that, while I think Barron wrote the right number of words, I think about half of them were the wrong words. Barron writes a lot of distractions, while giving the reader scant detail about what is actually happening, especially in magic sequences. For example, by the time a minor character in the first act was revealed to be an orisha in the third, I could not remember that character ever showing up in the first place. Barron’s writing should be perhaps not more focused, but certainly more pointed in showing what’s truly important among the thousands of fascinating details.

By day, Amy Tenbrink dons her supergirl suit and practices transactional and intellectual property law as an executive vice president for a media company. By night, she dons her supergirl cape and plans Sirens and reads over a hundred books a year. She likes nothing quite so much as monster girls, Weasleys, and a well-planned revolution.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter