Each year, Sirens chair Amy Tenbrink posts monthly reviews of new-to-her fantasy books by women and nonbinary authors. You can find all of her reviews at the Sirens Goodreads Group. We invite you to read along and discuss!

I was fully prepared to dislike Gideon the Ninth.

Because everyone loved Gideon the Ninth.

It’s not so much that I’m contrarian by nature—though I’m sure the patriarchy thinks I am—but that I have a list of speculative works as long as my arm that everyone loved and I really did not. Books that I quit at page 50. Books that I threw across the room at page 300. Books that I put down and forgot to ever pick up again. Books that I finished under duress. Books that I finished so that, in all seriousness, I could hate them properly. I will not name names.

But everyone loved these books.

I did not.

Everyone loved Gideon the Ninth.

I was fully prepared to not.

But will wonders never cease: I, too, loved Gideon the Ninth.

All the books I love have two things in common, regardless of genre or category or author or publication date: an unflinching defiance and a blazing ambition. These books that I love are rarely—but only rarely—perfect. Instead, these books often trip over the sheer force of their defiance or their ambition. And that is why I love them: I am far more interested in cataclysmic, rage-filled defiance and formidable, shoot-for-the-moon ambition than I am in perfection.

Which is to say that, if you’re trying to understand what I loved about Gideon the Ninth, you have to understand that I love White Is for Witching more than Gingerbread, and Who Fears Death more than Lagoon, and American Hippo more than Magic for Liars, and The Stars Are Legion even though I like neither space opera nor body horror, and Food of the Gods despite that it’s gore-strewn chaos, and Conservation of Shadows more than just about anything. My literary love is defiance and ambition, so much so that a messy book born of too much of either is far, far preferable to a perfect book born of less.

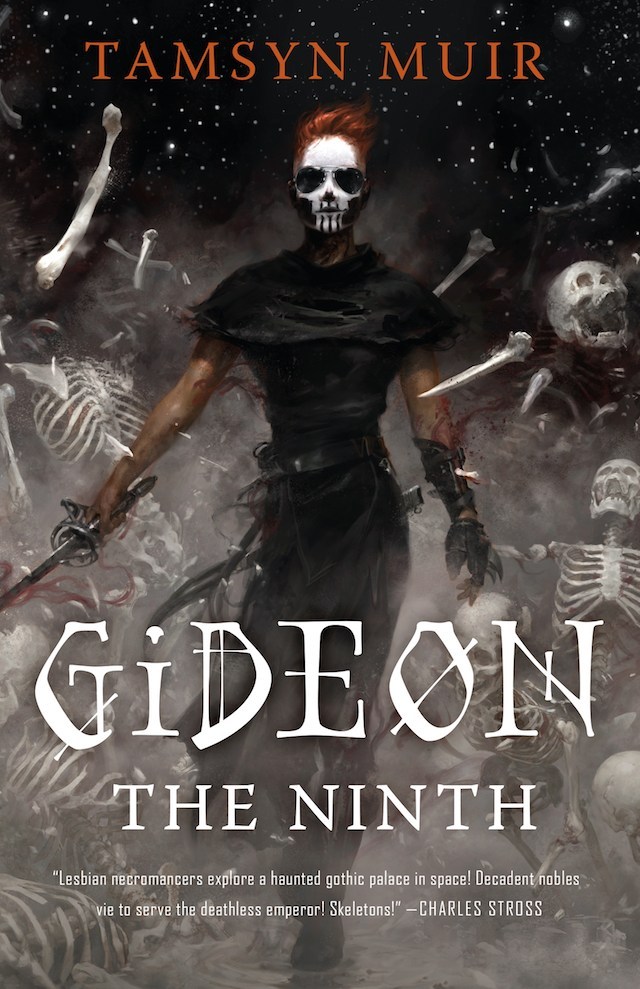

And while Gideon the Ninth is a number of things—including, yes, a story of lesbian necromancers in space—its heart is author Tamsyn Muir’s unrelenting defiance and ambition.

Somewhere in space, in some year, there are nine houses, eight beholden to the First, all adept at necromancy, all weird as fuck in a raw, all-id sort of way that reads as both endlessly fascinating and wholly authentic. People are weird, man, and consistent with basically everything ever, royalty-equivalent necromancers are weirder than most.

Gideon Nav is a foot-soldier in the Ninth House who really, really, really wants to leave the Ninth House’s planet and go far, far away and fight in a war she doesn’t really understand and maybe someday not be indentured to anyone, let alone to super-creepy Harrowhark the Ninth, Reverend Daughter of the Ninth House. Gideon and Harrow loathe each other, for reasons that it takes a whole book to explain, and as the book opens, Gideon is attempting to escape and Harrow wants her to stay and do her a favor. A challenge is issued and accepted. Neither Gideon nor Harrow plays fair—Gideon is tremendous with a two-handed sword, Harrow is perhaps best in the galaxy at necromancy, neither has many qualms or morals—but Harrow offered the rules, and though she and Gideon are relatively evenly matched, she tricks Gideon into acting as her cavalier primary for some weird-ass competition that the Emperor is throwing for the other eight Houses.

Shades of The Hunger Games abound, but Gideon the Ninth turns on distrust, cleverness, and gothic-style mystery more than desperation-fed, almost accidental revolution. Eight necromancers and their cavaliers primary—presumptively, each House’s intelligence and strength—are abandoned in an unknown building full of dangerous riddles and a single rule. Each necromancer is unfailingly ambitious, though each plays the game quite differently. Each cavalier primary is seemingly unfailingly loyal, except Gideon, who would frankly rather stab Harrow in the back with her teensy-weensy cavalier sword than help her solve riddles.

The heart of Gideon the Ninth is not lesbians nor necromancers nor space, but the fully realized relationship between necromancer and cavalier primary—a bond presumed closer than love, closer than blood—that Muir creates not once, but eight unique times. The generations of tradition that underlie these relationships, and the weight afforded to any breach of those protocols, are tangible. Much is made of the fact that Gideon was not trained as the Ninth House’s cavalier primary, but rather takes over from some wholly inept dude and learns a new fighting style. Much is made of the fact that Gideon rejects more traditional secondary weapons in favor of the close-range knuckle knife. More is made of the fact that, in Gideon’s first challenge as the Ninth House’s cavalier primary, her opponent disarms her and she retaliates by punching him. He goes down, gasping for breath, and a shocked spectator notes that he won the challenge, but Gideon won the battle, specifically by not following the rules.

And in that sort of exchange—which happens over and over and over again as Gideon or Harrow or both defy the rules, defy expectations, pursue their own desires, and ultimately reshape their own necromancer-cavalier primary relationship in a way that involves a leviathan sacrifice, but continues to subvert generations of history—demonstrates both Muir’s defiance and her ambition. Gideon the Ninth is not a revolution book (though the Locked Tomb series may well be), and yet it is: Because everything that Gideon or Harrow does, everything that Gideon or Harrow says, everything that Gideon or Harrow is—Harrow’s refusal to care about others, Gideon’s hilarious-yet-fully-felt insults, Gideon’s biceps, Harrow’s blood magic, Gideon’s sunglasses, Harrow’s face paint—is a defiant, ambitious revolution for the reader.

Rude, unlikeable, self-absorbed, brilliant, powerful women always are.

If you’re reading closely, you’ll be wondering right about now if Gideon the Ninth is a messy sort of book. It is. The world-building isn’t quite fully realized: I think it is in Muir’s head, but it didn’t quite make it on the page. The plot, particularly plot points surrounding the geography of the giant, gothic building they inhabit, is sometimes muddled. Going on twenty important characters, even if fully individual and fascinating, are too many people to keep track of, so you’ll breathe a sigh of relief when Muir starts killing them off. The necromancy magic is incomprehensible, though what matters for following the story is logic, not any real understanding of how the necromancers do what they do. It is, indeed, messy.

But if, like me, you’re less concerned with tidiness than you are with female characters who are defiantly unfettered by the rules that are meant to bind them, and Muir’s tremendous ambition in putting that on a page, you’ll love Gideon the Ninth, too.

Amy Tenbrink spends her days handling strategic and intellectual property transactions as an executive vice president for a major media company. Her nights and weekends over the last twenty-five years have involved managing a wide variety of events, including theatrical productions, marching band shows, sporting events, and interdisciplinary conferences. Most recently, she has organized three Harry Potter conferences (The Witching Hour, in Salem, Massachusetts; Phoenix Rising, in the French Quarter of New Orleans; and Terminus, in downtown Chicago) and ten years of Sirens. Her experience includes all aspects of event planning, from logistics and marketing to legal consulting and budget management, and she holds degrees with honors from both the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music and the Georgetown University Law Center. She likes nothing so much as monster girls, Weasleys, and a well-planned revolution.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter