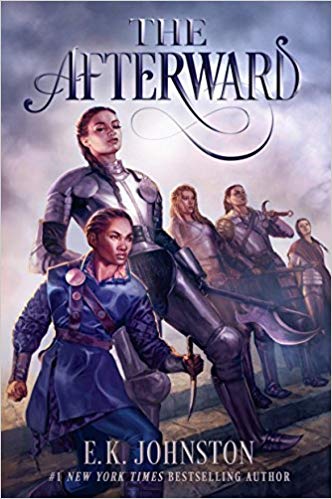

E.K. Johnston’s The Afterward (Dutton, 2019) is something of an odd duck in the current YA field, starting with its intentional 90s throwback cover. Although it’s explicitly cast in the vein of epic fantasy that was so popular then, and the book is dedicated to David and Leigh Eddings, the patron saints of latter day epic fantasy, it’s also a book about what comes after the endings of most traditional epic fantasy—namely, what happens once the world has been saved and the heroes find themselves still having to make their way in that world.

The book opens a year after a band of seven brave companions saved the world from the cursed godsgem: one of them is now Queen of Cadrium, others are retired or doing other things, but Apprentice Knight Kalanthe Ironheart and thief Olsa Rhetsdaughter have fallen right back into what they were doing before the quest. Although they have clearly outgrown those roles, there doesn’t seem to be anything else for them to do: Olsa was able to clear her debt to the thief guild, but as she has no other skills she is now an independent contractor, putting her in an arguably worse position, and Kalanthe is now awkwardly treated like a knight without having the actual rank of a knight. Both of them are isolated from their former peers, and they’re not getting along with each other too well either, despite the fact that they fell in love over the course of the quest. It seems like the setup for a queer and happy ending, but Kalanthe isn’t from a wealthy family, and she must marry a wealthy spouse to clear the debts she took on training for knighthood. For her part, Olsa’s fame means she is being set up as the fall guy for every job she takes, and she’s all too aware that she’ll end up in the noose sooner rather than later. Meanwhile, there are hints that the threat of the godsgem is not entirely ended; the “after” action unfolds alongside slices of what happened “before” the quest’s conclusion.

The problem of what comes after the end in epic fantasy is as old as epic fantasy itself; Tolkien himself began, and then abandoned, a “new peril arises in Minas Tirith!” tale set early in the Fourth Age, rightly recognizing that nothing could really live up to the threat of Sauron. Johnston’s solution to focus on the domestic and make the renewed peril of the Big Bad the secondary plotline largely works, partly because the question of whether Kalanthe will be able to follow her heart or whether she will have to enter into a marriage to a man against her wishes is a vexing one for her and for the reader (and for Olsa!). I’ve seen a lot of people complain that Johnston didn’t have to set up the society of Cadrium the way she did, with queer relationships accepted but the weight of inheritance law still behind heterosexual partnerships, and that’s certainly true. But it’s also kind of the point: the law lags social mores, and as much as the king and queen would like to change things including the debt system that allows non-wealthy children to become knights at all, it takes time to enact that kind of institutional change as well as willpower. Meanwhile, people have to negotiate with existing power structures as best they can.

Student debt has been much in the news lately, and as a member of the generation whose choices in life are vastly constrained by paying off education loans, I very much appreciated the way Johnston was able to marry certain real-world late capitalism issues, including the precarity of contingent labor, with her epic fantasy setting. I also appreciated the light touch with which she handled certain tropes of that setting, such as the obligatory thieves guild and wizard city, while also questioning them—probably my favorite character aside from the protagonists is Giran, the indigenous female apprentice scholar whose own knowledge and existence challenges the established hierarchy of scholarship and power in the university city.

Johnston has acknowledged that plot isn’t her strongest element as a writer, and that certainly holds true in The Afterward and in her other five novels I’ve read. Sometimes this lack is acutely felt, as in her Star Wars novel Ahsoka, but mostly it works for me in her chosen settings, and The Afterward definitely falls into the latter category: indeed, if the plot were more action-packed it might fall into the trap of trying to make the aftermath as exciting as the quest. I also appreciate the subtle radicalism of insisting that things like marriage, inheritance, and family are just as important as defeating the Big Bad, and I very much appreciated where the book wound up. Kalanthe and Olsa have struggled both together and separately through the course of the book, in both the before and the after, and seeing them get what they ultimately deserve is satisfying partly because it’s still so rare outside of fanfiction. The Afterward is worthwhile purely for its queer love story, but everything else it’s doing makes it an even more rewarding read.

Dr. Andrea Horbinski holds a PhD in modern Japanese history with a designated emphasis in new media from the University of California, Berkeley. Her book manuscript, “Manga’s Global Century,” is a history of Japanese comics from 1905–1989. She has discussed anime, manga, fandom, and Japanese history at conventions and conferences on five continents, and her articles have appeared in Transformative Works and Cultures, Convergence, and Mechademia. In her spare time, she edits video for fun and can be found tweeting as @horbinski.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter