AMY: For attendees who may not know your work, would you please tell us a bit about it? What is your field? What are your main areas of research? What topics do you teach? What issues do you love to discuss and deconstruct?

SUZANNE: My research sits at the intersection of fan and audience studies, media industry studies, digital culture studies, and feminist media studies. This is all just a long way of saying I’m interested in how media industry/fan relationships have shifted in recent years alongside the mainstreaming of both geek culture and digital technologies that allow culture to be more participatory and how gender shapes these relationships…for better and for worse. Much of my work focuses on boundary policing practices within fan communities, and who can more or less easily occupy the cultural category of “fan.” I joke that I teach the “geek culture” courses (video game studies, gender and fan culture, remix culture, a transmedia storytelling course that focuses on Star Wars, and so on), but really what I’m hoping students get out of my classes is an understanding of the politics of participatory culture, and the critical thinking and making skills to assert themselves within that culture.

AMY: What does heroism, especially in comic books or speculative work, mean to you? Does gender influence that definition?

SUZANNE: Heroism, at least from my perspective, is about the defiance of expectations. This is often manifested quite literally in things like superpowers, but I think more holistically all heroes force us to grapple with how the normative is entrenched, and our own relationship to hegemonic power. Hegemonic power, or the maintenance of sociocultural hierarchies, is all about people en masse buying into a sort of “common sense” logic that is undergirded by expectations about people that are raced, classed, aged, gendered, and so on. And it’s precisely because that work is speculative that I think it’s powerful. The speculative media I’m most drawn to takes place in the very near future, where the more dystopian elements represent a clear warning (we can understand, as audiences, how our sociopolitical failings in the present will bring us to this future) but also afford enough temporal leeway to shift gears and potentially right wrongs. Alternately, they can help us see our contemporary moment more clearly. Bitch Planet is one of those comics for me, which on the one hand makes a very compelling argument about the logical ends of growing antifeminist sentiment, but also clearly conveys who is most at risk in this culture, how identity shapes that, and also offers some nuanced critiques of how white feminism might counterintuitively be helping to fuel it.

AMY: Much of your recent work has been on heroism and bodies. And so much of your work for so long has been about the transformation of works when they reach the hands of fans, including the transformative work of cosplay. Talk to me about your work in this space: What is so important about the intersection of heroism and bodies, and how does that intersection change or evolve when you consider cosplay?

SUZANNE: One of my favorite things I’ve written is a piece on the Tumblr “The Hawkeye Initiative,” which is a fanart project that takes submissions of panels of female superheroes from comics that have been redrawn to feature the male superhero Hawkeye (often satirizing the initial representation both in back-breaking poses and skimpy costuming). It’s undoubtedly a fan activist effort, and I would argue a very effective one, in large part because it forces us to confront how desensitized we can become to this recurring imagery precisely because of its consistency over time. It becomes so commonplace that, while we might immediately recognize it as sexist or racist or sizeist or ableist, we don’t see any meaningful way to intervene. The fanart submitted to “The Hawkeye Initiative” ruptures that, and clearly conveys the absurdity of many of these poses and representations. Fans have a long history of using transformative works to comment on both a media object and culture at large, and this is one effort that I feel speaks both directly to comics book creators and the industry, but also comments more generally on beauty culture and norms.

My new book project I’m embarking on now is all about the fan body, both as a site of cultural anxiety and as a reflection of fandom as an emergent lifestyle brand. The key for me, here, is who gets to more or less easily occupy that body or capitalize off of that lifestyle brand. I’m excited, in part because I get to tackle issues of ableism, racism, transphobia, sizeism, and homophobia in ways I didn’t in my prior book, but also because I get to delve into things like food and nerdlesque (yes, that’s nerd burlesque) and cosplay and fitness. Heroic bodies feature heavily into this, particularly the fitness chapter, which surveys an array of “superhero” themed workouts and athleisure wear. I’ve just started researching and doing some field work (such as running a Wonder Woman themed 5K), but I’m already seeing some key distinctions in how the gendered superhero body as an aspiration fan body is presented.

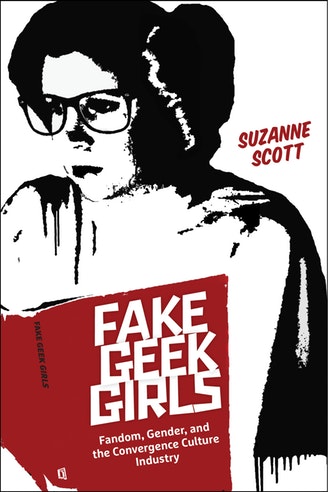

AMY: You and I have talked, repeatedly, about gender and fandom, often about how women and non-binary people are the oft-unsung heroes of fandoms, doing the lion’s share of the invisible labor necessary to create and maintain fandoms. And indeed, your brand-new book, Fake Geek Girls: Fandom, Gender, and the Convergence Culture Industry, is all about gender and fandom—and the frequent marginalization of female fans. In your view, what does the current evolution of gender in fandom look like, and where are we headed?

SUZANNE: I think my book tells one very specific narrative about how cishet white men have been conceptually centered within both industrial and fan-cultural understandings of the ascendance of geek and fan culture over the past decade and how that, in turn, has marginalized already marginalized fan identities and empowered small segments of that privileged fan demographic to often violently police the boundaries of acceptable or “authentic” fan identity. So, on the one hand, we have women being consistently told they are unwelcome or inauthentic fans in ways that range from overt harassment to subtle messaging by industry about who can more/less easily occupy that identity. On the other, I end the book stating that my OTP as a fan scholar is fandom and intersectional feminism, and talking a bit about fan fragility (a play on Robin DiAngelo’s discussion of white fragility). This is to say, I think there is a real and immediate need for white women within fan culture (and I absolutely include myself here) to grapple with their role in upholding systems of power that they benefit from, and considering the ways in which women might be performing similar exclusionary work.

AMY: Let’s talk about money and power, specifically commercialization and fan appropriation of speculative works. We all know that female characters disappear somewhere along the way to toy production and that I can buy a sexy Ghostbusters costume in two seconds from Amazon. Relatedly, we also know that if I want a Black-Widow-on-a-motorcycle action figure or a full-blown Jillian Holtzmann costume, I need a fan to create it for me. But there’s power in those fan creations, power that isn’t there in simply buying something off the shelf at Target, power in actively taking back the commercialization that major media companies won’t readily provide. Talk to me about money and power and fans.

SUZANNE: I’ve written about this mostly through the #wheresrey pushback on social media to the lack of merchandise surrounding The Force Awakens, but yes this has been an ongoing problem wherein fangirl consumers (and particularly young girls) get routed into heterosexist fan merchandising traps early and that persist over the lift course. The easiest shorthand for this would be a boy’s t-shirt that says something like “I want to be a superhero!” and the girl’s variant proclaiming “I only date superheroes,” and then eventually women’s merchandising proclaiming things like “Training to be Batman’s wife.” One thing fan scholars have and do continue to focus on in our work is how fan community spawns production cultures dominated by women, which remains a rarity. So, as you suggest in your question it’s not all gloom and doom. I look at all the female fantrepreneurs who are very pointedly making alternatives to that sort of merchandise and are building legitimate brands around these alternatives to mainstream fan merchandise. Now, much of this form of “fan empowerment” is still couched in neoliberal or postfeminist consumption, so issues of capitalism and class are still very much in play, but there is something generative in feeling like you are supporting an individual (one who may even be a part of a broader fan community) rather than a corporation.

AMY: Sirens is about discussing and deconstructing both gender and fantasy literature. Would you please tell us about a woman or nonbinary person—a family member, a friend, a reader, an author, a scholar, a character, anyone—who has changed your life?

SUZANNE: This is tough, as about twenty names of very real, very incredible women immediately came to mind. I’m going to go with a fictional (not to mention potentially controversial) choice, which is Cordelia Chase from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Now, for any who haven’t watched this series, Cordelia started out as a sort of stereotypically vapid rich bitch/mean girl foil, and eventually became a more nuanced character over time. That said, picking her has nothing to do with the character as it was represented on television, and everything to do with the fact that BtVS was the first digital fan community I participated in during the late 90s. I was a part of an IRC chat roleplaying collective where I portrayed Cordelia (as a newer member of the community, I wasn’t about to be trusted with Buffy), and it was my first time writing what was essentially collaborative, real-time fanfiction with a community of other women. That space was so special, because it exposed me to the transformative power of fannish textual production, and feminist fan spaces more generally (something that obviously has gone on to shape both my life and my research). Cordelia empowered me to rewrite narratives I found to be too facile, encouraged me to garner a deeper understanding of myself through identity play and performance, and introduced me to the ways in which fan works can function not only as media criticism, but media objects and art in their own right.

Suzanne Scott is an Assistant Professor in the Radio-Television-Film department at the University of Texas at Austin. Her current book project, Fake Geek Girls: Fandom, Gender, and the Convergence Culture Industry (forthcoming from NYU Press, 2019) considers the gendered tensions underpinning the media industry’s embrace of fans as demographic tastemakers, professionals, and promotional partners within convergence culture. Surveying the politics of participation within digitally mediated fan cultures, this project addresses the “mainstreaming” of fan and geek culture over the past decade, how media industries have privileged an androcentric conception of the fan, and the marginalizing effect this has had on female fans. She is also the co-editor of The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom (2018). Her scholarly work has appeared in the journals Transformative Works and Cultures, Cinema Journal, New Media & Society, Participations, Feminist Media Histories, and Critical Studies in Media Communication as well as numerous anthologies, including Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World (2nd Edition), How to Watch Television, The Participatory Culture Handbook, and Cylons in America: Critical Studies in Battlestar Galactica.

For more information about Suzanne, please visit the University of Texas Radio-Television-Film department website or her Twitter.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter