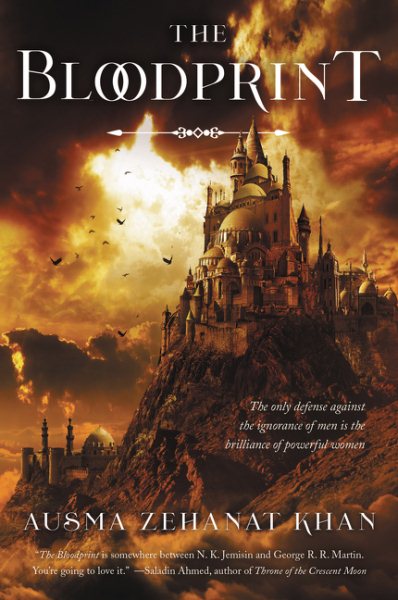

The Sirens Review Squad is made up of Sirens volunteers, who submit short reviews of books (often fantasy literature by women authors) they’ve read and enjoyed. If you’re interested in sending us a review to run on the blog, please email us! Today, in honor of Ausma Zehanat Khan’s Guest of Honor week here at Sirens, we welcome a review from Alyssa Collins on Ausma Zehanat Khan’s The Bloodprint.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about heroism. Given the general nature of literature since, well, forever, and the sheer amount of superhero movies on rotation, it’s generally unsurprising to be confronted with the concept. Still, I remain suspicious of heroes because of who they tend to be: white, male, Western, and overrepresented. Additionally, heroism is often bolstered by ideas of noble conquest, war, imperialism, nationalism, and other “-isms” I don’t enjoy. After years of reading and writing and teaching literature, this formula never fails to be grating, nay exasperating, even when I become fond of said male hero. Recently, however I was saved from this struggle when I picked up Ausma Zehanat Khan’s The Bloodprint.

The Bloodprint is a hero’s journey. The novel follows Arian, a Companion of Hira, who is on a quest to find a sacred and magical relic known as the Bloodprint. The Bloodprint is a part of the Claim, a fragmented, magical text whose interpretation or misinterpretation fuels both the violent misogynistic empire of the Talisman and the magic of the Companions. Along her journey she faces peril and possible romance, and must unravel the motivations of the First Companion and the politics of Hira.

By novel’s end, The Bloodprint ended up not being quite my cup of tea. The in medias res beginning is confusing, with worldbuilding details abruptly revealed instead of organically, and with an omniscient narrator disguised as third-person limited, mostly through Arian’s eyes. Stylistically, dark eyes flash, glances are thrown about the room, and plot twists and character reveals aren’t surprising for a seasoned fantasy reader. Still Arian, to her credit, is as principled as the most storied of holy men, answering to a higher cause and mission (called an Audacy) instead of her own worldly pleasures.

Yet, there are several things I really appreciate about Khan’s novel. For instance, The Bloodprint’s explicit politics and representation of oppression. The Bloodprint opens as Arian and her awesome archer-accomplice Sinnia liberate a group of enslaved women and dispose of their male slavers. Within a short action scene, the various geographies of the world are established, those of travel and movement and of society and oppressions. The misogynistic empire of the Talisman expands across an area based on what we know as Central Asia, and women under this regime are limited in movement, dress, and way of life. Khan makes the violent realities of this world explicit and Arian a noble hero fighting against them. I was excited to see a topography that I don’t often encounter, in addition to a hero who is a brave, smart woman explicitly fighting for her people against the misogyny and hate of terrible imperial power.

Also, the magic! Magic in The Bloodprint is encoded and empowered by language. Thus, interpretation is an incredibly powerful tool. As a reader, and professor of English, this resonated with me on several levels. First, the problem of misinterpretation of a religious text is one that afflicts the cultural, social, and political realities of the contemporary Middle East and Central and South Asia. Additionally, problems of interpretation and truth are concepts that readers in the early 21st century are becoming increasingly familiar with. How we read, understand, and use written language has never been more important. The Bloodprint is able to imagine through both a specific historical place and moment and expand outward in a recognizable way.

This kind of conceptual framing is where Khan really uses the tropes and traditions of high fantasy—imagining Christian narratives in new times and places—for new purposes. Readers who are familiar with the high fantasy of the 1980s and 1990s, especially fans of Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series, will find comfort, yet be challenged by recast players and places in order to experience a different imagined story of the Middle East and Central and South Asia: her provoking allegory as opposed to contemporary Western narratives that are often based in dismissal, Islamophobia, and imperialism. At the end of the day, Arian is a woman fighting for, not against, her people, and to succeed is to free them all.

Despite my own stylistic qualms (and the sudden cliffhanger of an ending!), The Bloodprint is an important book that continues to speak to the concept of heroism—who can be a hero, and who they should fight for—and asks readers to consider (or reconsider) their historical and cultural blind spots.

Alyssa Collins is an assistant professor of English and African American Studies at the University of South Carolina. Her work explores the intersections of race and technology as depict-ed in 20th century and contemporary African American literature, digital culture, and new media. When she’s not working, she writes about race, superheroes, television, and embodiment around the internet.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter