Each year, Sirens chair Amy Tenbrink posts monthly reviews of new-to-her books from the annual Sirens reading list. You can find all of her Sirens Book Club reviews at the Sirens Goodreads Group. We invite you to read along and discuss!

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the exchange between reader and writer.

I think we’re taught that if, as a reader, we didn’t connect with a book, it’s the writer’s fault. The writing wasn’t good enough. The story wasn’t true enough. The writer failed. And we, as readers, get to go on our merry way to other books that, maybe, wouldn’t fail us.

And before all the writers start fist-pumping and the readers start thinking that I’ve spit in their tea, there’s a lot of truth in that. Some writing isn’t good enough. Some books aren’t true enough. And while I wouldn’t say that writers necessarily have failed us, sometimes books do.

But sometimes, readers fail, too.

A few years ago, when Sirens tackled “hauntings,” and I read an awful lot of books about ghosts, I ran across a quote from Edith Wharton, herself a great lover of—and writer of—the ghost story: that she was conscious of a “common medium” between author and reader, where the reader actually “meet[s] [the author] halfway among the primeval shadows …” And I, who had been reading all of these ghost stories in sterile hotel rooms with their sterile lighting—which, in no one’s estimation, had any primeval shadows—took a moment to realize that, if I wanted to be scared by ghost stories (I didn’t), then I really should change my reading location (I didn’t). A stormy lamp-lit night might be a better breeding ground for the imagination required to truly appreciate Shirley Jackson than the New York hotel room where I actually read The Haunting of Hill House.

Which is a somewhat ridiculous example because, as many Sirens well know, my interest in ghost stories approaches zero. But this is true in a number of other instances as well. If writing doesn’t engage the reader, maybe it’s not the quality of the writing, but a failure of the reader’s focus. If the book doesn’t seem true to the reader, maybe it’s not the quality of the book, but a failure of the reader to recognize someone else’s truth. Or, you know, maybe it’s just a bad book.

Sometimes it’s hard to tell.

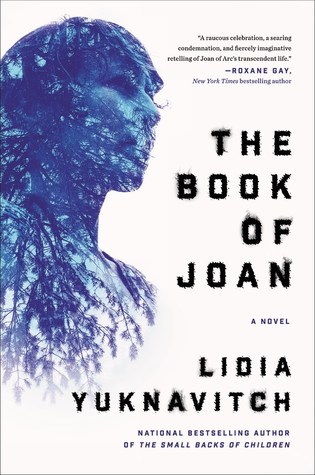

Which brings me to The Book of Joan by Lidia Yuknavitch.

Let me start by saying, categorically, that this is not a bad book. It’s a good book. I just had a hard time deciding if it’s a great book.

As a reader, I bounce hard off most sci-fi. It’s not you, sci-fi, it’s me—except dude, it is so often you. Someone asked me recently if I liked The Stars Are Legion, and I made a face and said that, while I respect it greatly (I do) and I think it’s a great book (I do), I also found it very damp. (Not that fantasy can’t be very damp, too.) My best friend tells me that I read the wrong sci-fi; I tell her that the right sci-fi seems somewhat unicorn-ish, not to mix metaphors.

To add insult to injury, I read most of The Book of Joan on a plane (usually fine) seated next to a toddler who very much wanted to talk about his big red truck (somewhat less fine). He was quite well-behaved, given that he was being asked to sit quietly in a seat for four hours. But he was chatty. So, so chatty.

And finally, maybe it wasn’t the right year for me to tackle The Book of Joan, which is fundamentally about, not to put too fine a point on it, the end of the world as we know it, a bossy totalitarian dude, and a Joan of Arc character who is supposed to either end the world or save it (sometimes it’s hard to tell). Maybe this year I could use some more escapism in my escapism?

But, all that said, even taking into account the many, many ways in which I failed The Book of Joan, I think it’s an important book, a good book … but not a great book. Let’s discuss.

Several decades in the future, war has devastated the earth and remaining approximation of humanity—virtually genderless, colorless computer ports—lives in a space station named CIEL. Our first narrator, Christine, has just turned 49, which means she’s a mere twelve months away from being recycled, if you will. As she begins her last year of existence, she also begins what she thinks will be her last act of resistance: telling the story of Joan, literally burning the words onto her own body.

Joan, you see, was the leader, the figurehead, the most visible of the “eco-terrorists,” or alternately the revolutionaries, the losing side in the war. (To the victor go the spoils and also the definitions.) When Joan’s side lost, Jean de Men (seriously), the leader of the winning side, had her burned at the stake—a method suitably flashy and final. Joan’s story remains in the hearts of those who resent Jean’s rule, and Christine intends to take this to the extreme, echoes of Joan’s fiery demise burned into Christine’s post-apocalyptic flesh.

SPOILER

But Joan didn’t die at the stake. Her friend and most constant companion, Leone, saved her, only for the two of them to wander the ravaged planet, alternately avoiding and fighting the other few thousand remaining people. As Joan’s story converges with Christine’s, an uprising, a second apocalypse, a re-birth, if you will, happens—and much is made about how the earth has survived much, though humanity as we know it has not. END SPOILER

The Book of Joan is largely experimental, vaguely feminist, with thinly explained worldbuilding, a non-traditional narrative structure, shifting points of view (made all the more confounding by the fact that both Joan and Christine use “she”), and tenuous timelines. So much of it is, more than anything, resistance-as-performance art, in a Russian nesting doll sort of way, as the climax of the book literally hinges on Christine’s performance art.

And for once—and I may never say this again—I wanted more book with more explanation. I didn’t need more plot, but I did find myself wanting more understanding, more details. How did we turn into neutered, hairless, space-dwelling creatures only a few decades in the future? How did our technology evolve so quickly? How did Leone save Joan from the stake? In many ways, this reads less like sci-fi and more like a religious text that demands that we accept things on faith—which may well be the point.

Which is the (very) long way of saying that, in the end, The Book of Joan worked for me (sometimes) as commentary, as an interrogation of faith and humanity and truth, but rarely worked for me as a story. The sole exception to that, incidentally, was Joan’s relationship with Leone, which gutted me several times, for many of the same reasons that Maddy and Queenie’s relationship in Code Name Verity gutted me. The denouement of The Book of Joan feels right and good and heartbreakingly terrible.

Amy Tenbrink spends her days handling strategic and intellectual property transactions as an executive vice president for a major media company. Her nights and weekends over the last twenty-five years have involved managing a wide variety of events, including theatrical productions, marching band shows, sporting events, and interdisciplinary conferences. Most recently, she has organized three Harry Potter conferences (The Witching Hour, in Salem, Massachusetts; Phoenix Rising, in the French Quarter of New Orleans; and Terminus, in downtown Chicago) and eight years of Sirens. Her experience includes all aspects of event planning, from logistics and marketing to legal consulting and budget management, and she holds degrees with honors from both the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music and the Georgetown University Law Center. She likes nothing so much as monster girls, Weasleys, and a well-planned revolution.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter