We’re pleased to bring you the third in a series of candid, in-depth interviews with this year’s Sirens Guests of Honor. We’re covering a variety of topics relevant to Sirens with each author, from their inspirations, influences, and craft, to the role of women in fantasy literature, and discussing our 2018 theme of reunion, as well as the themes of our previous four years: hauntings, rebels and revolutionaries, lovers, and women who work magic. We hope these conversations will be a prelude to the ones our attendees will be having in Beaver Creek this October! Today, Amy Tenbrink interviews our third guest of honor, Violet Kupersmith.

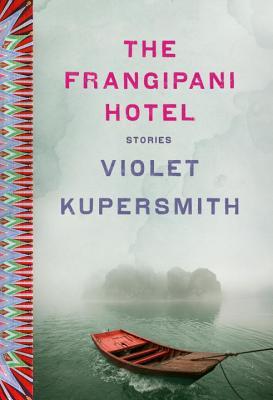

AMY: Women have a long history with ghost stories, from using them to examine cloaked feminine themes to finding themselves in the strange position of, after establishing the genre in the 1800s, now needing to reclaim them as our own. Why did you choose ghosts, hauntings, and horror as your medium for your work in The Frangipani Hotel?

VIOLET: In my family, only women see ghosts. I think this is part of the reason why I was drawn to them when I started writing about Vietnam and the Vietnamese diaspora. In the American imagination the dominant narratives about the war and its legacy are Western, male, and soldier-centric, so I set my stories in the realm of the supernatural—one of the few spaces where the rules aren’t set by men. Ghosts can act as a stand-in for female characters, giving them agency in a society where they are denied it, and working in the horror genre allows me to shine a light on the kinds of Vietnamese and Vietnamese-American characters who are scarred by the war but generally overlooked in stories about it: women in nursing homes, first-generation teenagers who work at grocery stores, long-haul truckers. In so many ways, the Ghost is the perfect metaphor for the immigrant: both are liminal beings, hovering between worlds, and here, both are feared and other-ed. And I think that there’s something fitting about using a literary genre which is often unfairly dismissed as silly or lowbrow to tell stories about a marginalized people. Each is able to empower the other.

AMY: Your work frequently, and often subversively, explores culture: its transformation following devastation, its vital connections, its loss and sometimes desperate preservation as people’s lives change. In “Skin and Bones,” Thuy eats her culture, literally, and finds a connection she didn’t think was there through Vietnamese foodways, while the American grandchild in “Boat Story” seeking an “A-plus” refugee story, hears an account of her immigrant grandparents and a boat, yes, but not one she ever expected. Conversely, your work, too, is often about invasion of culture: the American expansion in “The Frangipani Hotel,” where a single American businessman, looking for a Vietnamese woman to take out on the town, stands in for hundreds of thousands of American soldiers; or the American ex-pat in “Guests,” who can’t see her own condescension in her artificial competition with Vietnamese girls for her boyfriend. On your website, you share a bit about your family’s experiences and legacy. For you, how do written versions of stories intersect with the history and culture that you’re writing about?

VIOLET: My stories definitely feed off of my own neuroses about the place my ambiguously-brown Amerasian self occupies between these two cultures, and my hyper-awareness of the fact that I exist because of cruel historical circumstances that put my mother on a boat to America, where she met my father. I’ve always felt a bit like an amphibian, able to move between both worlds but never belonging wholly to either. When I started writing what would eventually become The Frangipani Hotel there was this common assumption, from both my relatives and from outsiders, that the pinnacle of the collection would be something like “My Refugee Family’s True and Terrifying Boat Journey,” that it was the ‘big story’ I had inside me and had been waiting to tell. And I bristled at this. I did want to honor my family’s legacy, but on my own terms. I’ve threaded their experiences into my books in fragments, because our story is one of brokenness, not boats. It started long before they left the shore and it’s still unraveling.

AMY: The Vietnam War is woven into every inch of The Frangipani Hotel, sometimes as a literal intrusion as in “Descending Dragon,” but more often as a looming shadow of memory or of devastation. Even—or perhaps especially—the American businessman in “The Frangipani Hotel” reads strongly as the personification of a modern-day capitalist invasion, a deliberate echo of American soldiers, while the Vietnamese men of “One Finger” relive their war-time horror in exacting, horrifying detail. How do you prepare to write work that, like this, is so inherently tied to such a complex, horrific tragedy?

VIOLET: To me, the Vietnam War is like a big, metaphorical black hole. You can’t see the thing itself; instead you see the material bending around it, the light that’s being sucked in. And that’s how I approach writing about it as well—I know that if I, personally, set out to write a realistic story about a bombing, or a battle, I would never be able to capture it in a way that would feel true to the reader, or give it the emotional gravity it deserves. I can’t face it head-on. This is another reason why I turned to the supernatural in my fiction—it lets me avoid writing explicitly about war while doing exactly that, on some level. The ghosts act as both a kind of shield and a conduit. I have to make monsters of my own in order to address the real ones in the country’s history.

AMY: You lived in Vietnam for a number of years, and spent much of that time exploring Vietnamese folktales and, I imagine, researching The Frangipani Hotel. What did you love about Vietnam? What surprised you about Vietnam? How did Vietnam change your writing and your stories?

VIOLET: Sometimes I hear myself talking about Hanoi and I realize it sounds like I’m talking wistfully about an ex-lover. It’s embarrassing. I can’t think of a way to say this that doesn’t sound silly, but I think Vietnam is just enchanted. Old-school, Brothers Grimm-style enchanted—equal parts dangerous and divine. The entire country seems to run on a dreamy and feverish, ‘It’s-4 AM-and-anything-could-happen’ kind of energy, for 24 hours a day. Everybody you meet has at least one truly weird story that they’re willing to tell you. And there is no other place on earth that has better food (there is a reason why the character in my stories I identify with most is sandwich-gobbling Thuy). The biggest surprise was a sad one. I arrived expecting that when I encountered discrimination it would be because of my Americanness. I was prepared to bear this. But instead, every time it was because I was a woman. The anger that I’ve felt about this, in particular, has seeped into my writing; my upcoming novel is simmering.

AMY: The nine stories included in The Frangipani Hotel explore a veritable mountain of themes: modernization and reclamation of folktales, an unmistakable indictment of the Vietnam War, the legacy of suffering and loss, the preservation of culture, everyday spirituality as immutable tradition, and about a thousand more. Of all the themes in your work, which do you most hope readers will discover and consider?

VIOLET: I think that in each of the stories the reader can latch onto the idea of inheritance, of what we are handed down—regardless of whether or not we want it or even feel we deserve it—from our parents, our parents’ parents, our nations. The skins, stories, memories, and trauma that we are given, the dangerous weight of these inheritances, and the lengths we have to go to in order to free ourselves from them. And I think that buried within this theme is an even trickier question: what we are owed by our histories, and what do we owe them? This was what I was attempting to answer when I wrote The Frangipani Hotel, and what I hope readers will ask themselves too.

AMY: Sirens is about the remarkable, diverse women of fantasy literature. Would you please tell us about a woman—a family member, a friend, a reader, an author, an editor, even a character—who has changed your life?

VIOLET: My mother is four-foot-ten and—I do mean this as a compliment—she is the scariest person I know. She is a survivor, a scholar, and an activist, and she possesses the kind of fearlessness that I can only write about. Growing up, she always gave in when I demanded bedtime story after bedtime story after bedtime story. Ghosts do occasionally talk to her. She is a remarkable woman in every way.

Violet Kupersmith is the author of The Frangipani Hotel, a collection of supernatural short stories about the legacy of the Vietnam War, and a forthcoming novel on ghosts and American expats in modern-day Saigon. She spent a year teaching English in the Mekong Delta with the Fulbright program and subsequently lived in the Central Highlands of Vietnam to research local folklore. She is a former resident of the MacDowell Colony and was the 2015–2016 David T.K. Wong Fellow at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England. Her writing has appeared in No Tokens, The Massachusetts Review, Word Vietnam, and The New York Times Book Review.

For more information about Violet, please visit her website or Twitter.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter