Each year, Sirens chair Amy Tenbrink posts monthly reviews of new-to-her books from the annual Sirens reading list. You can find all of her Sirens Book Club reviews at the Sirens Goodreads Group. We invite you to read along and discuss!

Are you familiar with The Tempest, Shakespeare’s storm-swept comedy full of revenge and magic?

I wasn’t.

While I will happily deconstruct prophecies and the self-fulfillment thereof in Macbeth for hours and I can still quote entire passages of Julius Caesar that I learned almost 30 years ago and I once dated a Hamlet for five long years of indecision, I have yet to meet a Shakespeare comedy that I like. This dates back to, of course, my first Shakespeare encounter in ninth-grade English: Romeo and Juliet, which you’re about to tell me is not a comedy, to which I will respond, “Only the parts that I loathe.” Bring on the death, please, and leave the purportedly funny coincidences out of it.

I still have not read The Tempest, incidentally, but the Internet was kind enough to tell me all about it: The white magician Prospero, inhabiting a deserted isle with his white daughter Miranda and a “savage” black boy named Caliban, who is the son of the dead witch Sycorax. Prospero contrives to bring those who exiled him to the isle, to be shipwrecked by a magical storm. Stuff happens, Miranda marries a prince of Naples, and all is well with the world.

Or something.

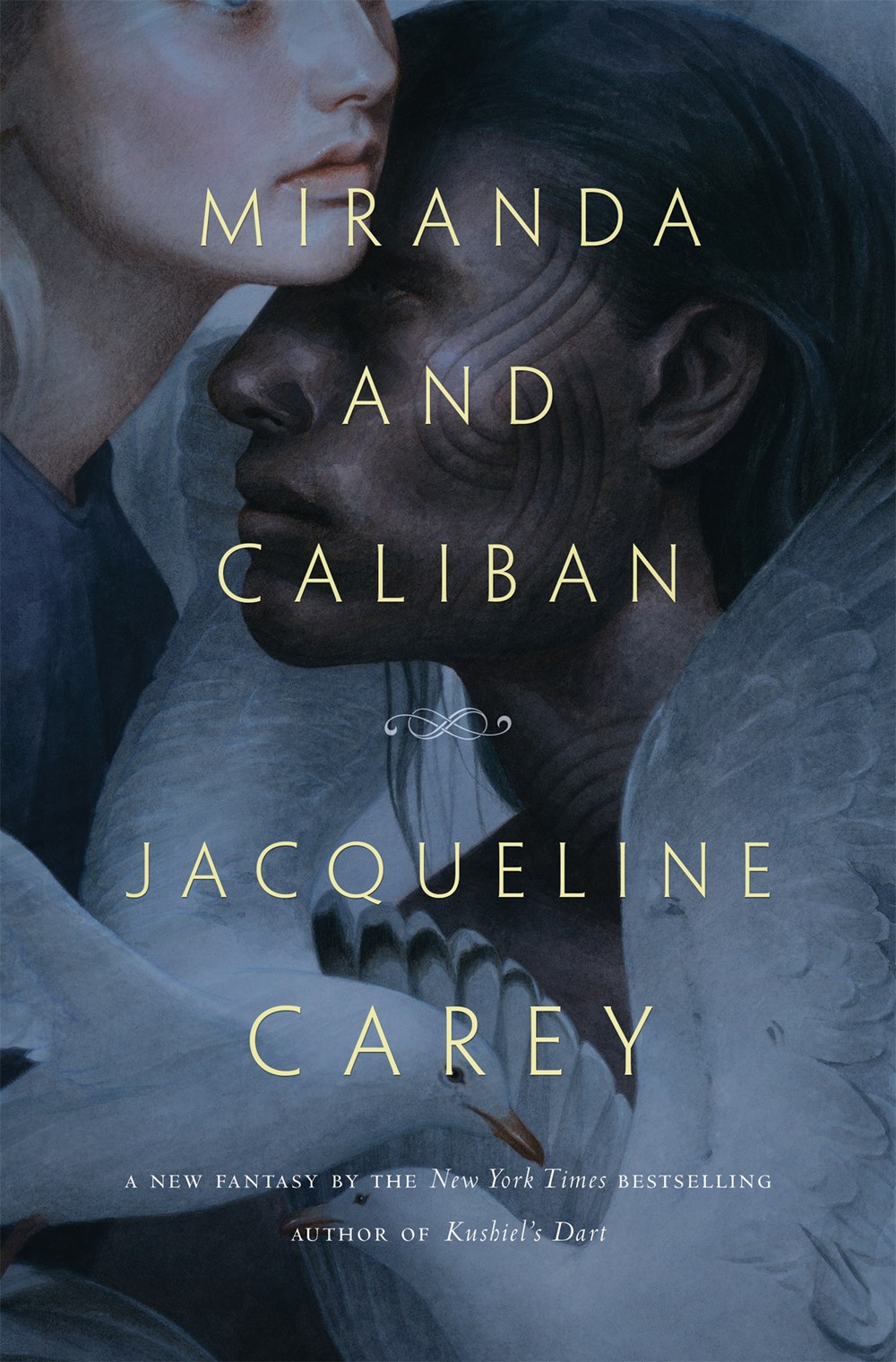

Jacqueline Carey’s Miranda and Caliban interrogates The Tempest, which one might presume, even from the brief summary above, is in need of a good interrogation. Miranda and Caliban opens several years after Prospero and Miranda’s exile to the isle: Miranda is a child of six or so, while orphaned Caliban is, at best guess, several years older. Very early in the book, Prospero works magic and compels Caliban to appear, only to lock him in a room in the hopes that confinement will impart refinement: language, posture, chamber pot usage, religion, and such. As you consider this, please remember that Prospero and Miranda are white, and Caliban is black.

Miranda’s gentle tutelage succeeds — for some value of “succeeds” — where Prospero’s aggression fails: Caliban learns their language and what is expected of him in this strange, new world ruled by an ill-tempered magician. Caliban eventually earns some measure of freedom — remember, though, that Prospero summoned him in the first instance, so “freedom” here is misleading notion — by supplying the name of the “evil” god that his mother worshipped. Prospero uses that name to free the wind spirit Ariel from a tree, only to bind him, too, to servitude.

As they age, Miranda and Caliban become friends, though it’s never clear if their friendship is born solely of their lack of options. Even after Ariel is freed from the tree, he’s mercurial, temperamental, and manipulative, not suitable for friendship for either Miranda or Caliban, and as you might expect from a volatile spirit in a Shakespeare play, in the end, Ariel’s impact on Miranda and Caliban’s friendship exceeds even their own. But Caliban remains Prospero’s servant, Miranda remains Prospero’s deliberately ignorant daughter, and Prospero’s plotting continues apace.

When Miranda blossoms, if you will, into a woman, Miranda and Caliban’s relationship changes. She menstruates for the first time, and thinks she’s dying. Her father gives her the world’s worst feminine hygiene contraption and collects her menstrual blood for his own magical purposes. (EW.) Caliban catches a glimpse of Miranda naked, and begins to understand the changes in his own body, only to be caught masturbating by Ariel, who calls him rude and savage, a monster. Miranda and Caliban attempt to consummate their relationship, only to be interrupted by an enraged Prospero, informed by a tattling Ariel.

Eventually, Prospero’s opportunity arises and Miranda and Caliban catches up with The Tempest: a magical storm, a shipwrecked boat, a betrothal, and Miranda sails away from the isle, leaving Caliban behind, but not without perhaps hollow promises to send for him when she’s a princess of Naples.

As I mentioned above, The Tempest is in need of a good interrogation. In the end, however, I found that Carey’s attempt was perhaps too gentle for me. I wanted more pointed criticism, more explicit condemnation of Prospero’s abuse and control of both Miranda and Caliban. I wanted some discussion of Sycorax other than, essentially, “the evil witch that used to live here, but she’s dead, and good riddance.” I don’t require a different, more thoughtful, more progressive ending, but I wanted a lot more deconstruction and complexity in getting there.

That said, I’ve been considering lately that simple truth-telling might be its own form of feminism. Sarah Pinborough’s Poison, for example, is a retelling of Snow White that (arguably) ends more poorly for Snow White than the fairytale itself. One might argue that that’s not feminist, simply because things go so badly for Snow White, but I find that that sort of truth-telling — here’s how things would actually go and they’re worse than you thought — is ultimately feminist.

While I might find the feminism in Miranda and Caliban less pointed than I would like, there is, at least, a form of truth-telling in it: Prospero’s use of his daughter for his own ends, Prospero and Ariel’s endless, on-page racism, Caliban’s enslavement. Explicitly marking these issues, if not addressing them fully, is perhaps its own form of feminism, even if it isn’t mine.

Amy Tenbrink spends her days handling strategic and intellectual property transactions as an executive vice president for a major media company. Her nights and weekends over the last twenty-five years have involved managing a wide variety of events, including theatrical productions, marching band shows, sporting events, and interdisciplinary conferences. Most recently, she has organized three Harry Potter conferences (The Witching Hour, in Salem, Massachusetts; Phoenix Rising, in the French Quarter of New Orleans; and Terminus, in downtown Chicago) and eight years of Sirens. Her experience includes all aspects of event planning, from logistics and marketing to legal consulting and budget management, and she holds degrees with honors from both the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music and the Georgetown University Law Center. She likes nothing so much as monster girls, Weasleys, and a well-planned revolution.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter