Each year, Sirens chair Amy Tenbrink posts monthly reviews of new-to-her books from the annual Sirens reading list. You can find all of her Sirens Book Club reviews at the Sirens Goodreads Group. We invite you to read along and discuss!

In 2009, on the very first evening of the very first Sirens, Tamora Pierce presented our very first Guest of Honor keynote address. And for more than three hours – long after many of the East Coast Sirens attendees went reluctantly to bed – Tammy regaled Sirens with her personal history of women in feminist fantasy literature: books and authors that she loved and that had changed her perspectives as a writer.

I often think that, were I do give my version of Tammy’s speech, my personal history of women in feminist fantasy literature would start, with few exceptions, around the year 2000. I read young-readers fantasy as a kid: Mary Poppins, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, The Wizard of Oz. I encountered Narnia in junior high, stubbornly plowed my way through Tolkien in high school, and then more or less abandoned fantasy until after law school. I missed Tammy’s work for decades – not to mention the work of pretty much every other woman who published fantasy books before, give or take, the year 2000. I came back to fantasy through YA: Harry Potter, Tithe, and Tammy’s later work.

But it’s interesting, isn’t it? How reader preferences change over time? How reader expectations change over time? I am rather well-read in the women-in-fantasy space post-2000. I read widely, voraciously, across subgenres and categories. But I still haven’t gone back to pick up many of those fantasy works publishing prior to 2000. Which is challenging because, as any historian will tell you, how can you possibly understand where we are if you don’t understand where we were?

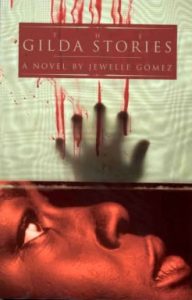

In 1991, most of the published fantasy works by women were high fantasy adventures, often with quasi-romance covers, about white heroines, with white male lovers, in often exclusively white fantasy worlds. And in 1991, Jewelle Gomez didn’t just storm into a breach in that history: she created an incredibly wide breach of her own.

The Gilda Stories features a protagonist that is black, a lesbian, and a vampire. It depicts slavery. It addresses racism and homophobia. It is unrepentantly feminist. It has a profound, prominent theme of found family. As Gomez explains, the book was rejected over and over again, including by a publisher who stated: “The character is black. She’s a lesbian. And she’s a vampire. That’s too complicated.”

I believe – and often proclaim at Sirens – that the very best thing about fantasy literature is the opportunity to create a world that addresses all the exclusionary issues so prevalent in our own: to allow women to rule, to allow lesbians to love, to allow heroes to have brown faces, to allow a variety of strengths and ambitions and powers. To center a novel around a black, lesbian vampire. And yet, Gomez says, “In the first round with Gilda, I had to convince people that it was a legitimate genre for me to use for the stories I had to tell.”

So let me tell you a bit about Gilda, in the hopes that you’ll add it to your own personal history of feminist fantasy literature:

Gilda opens in Louisiana in 1850. Our then-unnamed protagonist is found, having killed a man who tried to rape her, by Gilda: a powerful woman who runs a brothel. Our protagonist goes to work in the brothel, not as a sex worker, but as a sort of Girl Friday, doing odd jobs. She forms a powerful relationship both with Gilda and Bird, Gilda’s Native American lieutenant and lover. Not to give too much away, but Gilda and Bird are vampires and turn our protagonist into a vampire as well – almost simultaneously with Gilda’s deciding that she’s finished with life. She commits suicide, and somewhat strangely, our protagonist takes her name.

Gilda is told linearly, but not consecutively: a series of stories that depict Gilda’s unending life across both two centuries and much of the United States: from Louisiana to California to Missouri to New York City to New Mexico. Along the way, Gilda struggles to figure out, well, life – and the irony of a vampire figuring out life is half the beauty of the conceit. How to find family when you’re immortal? How to love? How to kill? Whether to bring anyone else into the vampire life? How to move past regret? What she hopes for the future? How to be something “other” in a world that values homogeny?

Where Gilda stumbles is the writing. While Gilda’s story is fundamentally fascinating – her hard-won wisdom, her evolution, her assembling her family – it’s hard to connect with Gilda. The book keeps the reader at a distance, often telling rather than showing, and sometimes moving at snail’s pace while we spend pages wrapped in Gilda’s head. The book could have used a stronger editing hand, to address both the aforementioned issues, but also to clean up the text: for example, almost every character in the book is a woman, and the feminine pronouns often lead to reader confusion.

But none of that diminishes Gilda’s place in the history of feminist fantasy literature: its profoundly intersectional approach twenty-five years ago. What do you think? Will you add it to your personal history of feminist fantasy literature?

Amy

Amy Tenbrink spends her days handling content distribution and intellectual property transactions for an entertainment company. Her nights and weekends over the last twenty years have involved managing a wide variety of events, including theatrical productions, marching band shows, sporting events, and interdisciplinary conferences. Most recently, she has organized three Harry Potter conferences (The Witching Hour, in Salem, Massachusetts; Phoenix Rising, in the French Quarter of New Orleans; and Terminus, in downtown Chicago) and six years of Sirens. Her experience includes all aspects of event planning, from logistics and marketing to legal consulting and budget management, and she holds degrees with honors from both the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music and the Georgetown University Law Center. She likes nothing so much as monster girls, Weasleys, and a well-planned revolution.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter