We’re pleased to bring you the first in a series of candid, in-depth interviews with this year’s Sirens Guests of Honor. We’ll cover a variety of topics relevant to Sirens with each author, from their inspirations, influences, and craft, to the role of women in fantasy literature and forms of resistance in both the craft and industry, as befits our 2015 focus on rebels and revolutionaries. We hope these conversations will be a prelude to the ones our attendees will be having in Denver this October! First up, Faye Bi interviews Kate Elliott.

FAYE: Kate, you’ve been writing fantasy and science fiction since the 1980s. In recent years, epic fantasy in all forms has seen more mainstream and critical success, with Game of Thrones winning Emmys and Sad Puppies garnering the attention of Entertainment Weekly. How has the readership of fantasy changed or expanded? And what has been your experience as a woman writer of fantasy during this time?

KATE: From my perspective one of the most interesting changes over the last few decades has been the mainstreaming of science fiction and fantasy (“SFF”) in popular culture. Although some SFF novels have always made the bestseller lists, they were not (in my experience) mainstream, but always a niche market that just, on occasion, happened to briefly impinge on the bigger pop culture market. Few people I met had heard of Dune; a few more might have heard of The Lord of the Rings but many fewer read it. SFF remained a corner inhabited by those of us who liked “that kind of thing” while meanwhile most people didn’t know it existed or (commonly) they thought of SFF as something childish.

KATE: From my perspective one of the most interesting changes over the last few decades has been the mainstreaming of science fiction and fantasy (“SFF”) in popular culture. Although some SFF novels have always made the bestseller lists, they were not (in my experience) mainstream, but always a niche market that just, on occasion, happened to briefly impinge on the bigger pop culture market. Few people I met had heard of Dune; a few more might have heard of The Lord of the Rings but many fewer read it. SFF remained a corner inhabited by those of us who liked “that kind of thing” while meanwhile most people didn’t know it existed or (commonly) they thought of SFF as something childish.

The incredible success of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series beginning in 1997 became hugely influential in the explosion of young adult (“YA”) and middle grade (“MG”) fantasy/fantasy-tinged fiction that happened in the decade of the aughts and which is still with us today. Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Laurel K. Hamilton were both precursors to the rise of urban fantasy and paranormal romance as a major publishing phenomenon as readers got to see and expect women main characters who both kicked ass and enjoyed hot romantic encounters in worlds filled with unpredictable encounters.

The arrival of the Peter Jackson-directed The Lord of the Rings on the big screen from 2001-2003 began a breakthrough for widespread visibility for fantasy in popular culture but even so fantasy qua fantasy—what I would call the hardcore epic fantasy—didn’t hit the big time until HBO’s adaptation of Game of Thrones, which is now, of course, a worldwide phenomenon. How great is it that Bollywood is doing its own version now? Pretty great.

Science fiction is mainstream now, and the big summer blockbusters feature superheroes. The genre has taken over.

But I don’t even think this is new or particularly unexpected. “Realism” or modernism or whatever you want to call it (and it’s a fine thing) feels more like a detour than a foundation. Historically the epics with their driven heroes, strange supernatural creatures, magical encounters, and fantastic adventures are the rice porridge (or meat and potatoes) of human storytelling. I think the rise of SFF as staples of 21st century popular culture can be seen more as a return to the kinds of stories people have always told and enjoyed, since before the written word.

But what does that mean for the “genre”? Genres are marketing categories created by the needs of businesses to make it easier for readers to find what they are looking for. Has the explosion of SFF into pop culture floated all the boats in the SFF genre? I don’t know. Lots is being published, more than ever before and exponentially so when we include all the self published works now available due to the miracle of digital publishing.

I do think that I see more fantastical and speculative elements all over everywhere in works that might have lacked them before, or more properly I guess I would say that books and TV and film are being made now that mash up categories in ways that might not have happened twenty years ago. I can’t help but think this is a good thing, although it does not help every writer.

My experience as a woman writer has been complicated. In the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s many women entered the SFF field and changed it in important ways, often with innovative works that, alas, have rarely been defined as innovative. Writers like Melanie Rawn, Anne McCaffrey, and Laurell K. Hamilton were bestsellers, and there was a push to find and market “Women in Fantasy.” Male writers have always been the biggest sellers in the epic fantasy market but there were always a fair number of women writing successfully in the sub-genre of fantasy as well.

This is just my observation, and I don’t have statistics to back up my statements, but it does seem to me as if about ten or 15 years ago a split started to happen with the rise of urban fantasy and YA/MG as strong genres in their own right (not that children’s literature hasn’t always been strong in its own right, but YA has become a real phenomenon in the publishing field in the last 10 years). It seems as if “epic fantasy” (however we are defining that) has become more identified with and highlighted by new male authors, while women have debuted into urban fantasy, paranormal, and YA. To some extent this reminds me of how, when my children were young in the 1990s, the toy aisles in stores were toy aisles and how, in the last ten years, retailers actually began to code aisles in stores with pink or blue as if boys must be dissuaded from ever walking down a “pink” aisle and girls from every glimpsing the mysteries that lies along the “blue” aisle. I admit it: I don’t like this. It not only commodifies gender but doubles down on the idea that gender and gender presentation and interests are unbreakable wires burned into our DNA when actually the pink and blue toy aisles in USA retail stores represent nothing more than an eye blink of cultural history as represented by a very narrow band of USA media/mainstream “values” built on an extremely rigid and narrowly based foundation.

Will that change? Is it changing? It’s too early to tell but I do know there is a lot of discussion about it online. The next generation is going to make its own rules (as always) so it will be interesting to see how this unfolds as we watch more and more women-led films and TV shows (once considered box office poison) lead the earnings numbers.

In many ways we are in a golden age of fantasy fiction. I suspect that as the lines between genres continue to blur and as other media continue to interact with print we’ll see major changes that we can’t yet predict.

FAYE: The summer before my freshman year of high school, I read the first five volumes of your Crown of Stars septology (those were all that were out!). I’d always been a fan of fantasy, but yours were some of the first adult books of fantasy I’d read. After that—I’d found Terry Brooks, David Eddings, and other dude fantasy authors in the library’s genre section. At that age, it never occurred to me to seek out female authors and creators. What epic fantasy works by women would you recommend?

KATE: This is the hardest question because any time I start listing recommendations I know I will leave out writers, and it is my considered opinion that one of the obstacles women writers (and writers along other diverse vectors) face is invisibility. Even in 2015 people still say, “but women don’t write epic fantasy.” I’ll be honest. Every time I hear that statement I may roll my eyes, because it’s so absurd, but it also hurts a little because by any possible definition I write epic fantasy and have been doing so for (as you point out) years. (In fact, now I feel old. OLD, I tell you.)

First, how are we defining epic fantasy? Massively long multi-part series set in historical-type settings, but with the addition of magic, fantastical creatures, and an empire- or earth-shattering conflict? Or any long fantasy, maybe in parts but maybe not.

I don’t have a definitive definition and I don’t think anyone does or ever could. I would urge every reader to seek out new worlds . . . and writers new to them. Exploration is half the fun.

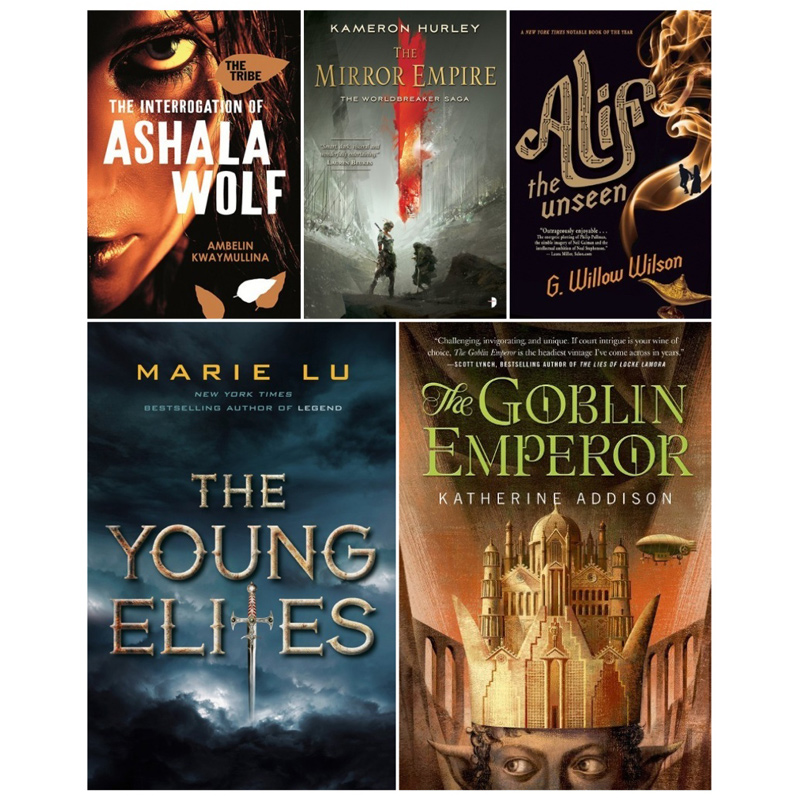

Strangely enough, this thread from 2014 over on Reddit mentions a LOT of names. With great trepidation I’m going to mention five names only with the understanding that there are many, many, many works I love out there, and far more I haven’t (yet) read. I’m choosing these as examples to branch off from and it actually pains me not to make a comprehensive list of 100 or 150 writers because I want to salute all the people. Please understand that I bitterly regret each writer who isn’t mentioned here. Please seek them out. They are fabulous.

Barbara Hambly’s The Time of the Dark trilogy from the 1980s. Grimdark before the term was being used to describe male-written gritty fantasy. This is a portal fantasy about two people from our world pulled into a very dark and grim world indeed. A classic.

Katharine Kerr’s 1986-2009 Deverry series (start with Daggerspell but make sure it is the revised version). A complete series of 15 books with a story highlighting how actions have consequences that unfold across lifetimes (it used reincarnation as a theme before Robert Jordan did). A fully detailed world, memorable characters . . . just read it.

Michelle Sagara West’s The Sun Sword (1997-2004) six-book series. Empires at war, demons invading from another dimension, and one of the most intense examinations of how duty and loyalty bind people together and tear them apart. This is dense and often slow moving, and rich in characterization and setting. There are also both prequel and sequel series to The Sun Sword, but I’m starting you out slow. For “lighter” fare by the same author, try her “Cast In” (Chronicles of Elantra) series.

N. K. Jemisin: Some might argue that her books aren’t long enough in word count to qualify as epic but her Inheritance Trilogy is about a war among the gods, for goodness sakes. How can that not be epic? Jemisin is a consistently vivid and smart writer, and I loved the Inheritance Trilogy and her The Killing Moon duology, so naturally I also look forward to her new series which launches in August and is about cataclysmic events that shatter civilizations, The Fifth Season.

Marie Lu is one of many newer writers who have made their careers in YA when, twenty years ago, they might well have debuted in adult SFF. Her The Young Elites is a strong fantasy with chaotic magic, rival factions, and a girl who may become the villain we should all fear.

I’m only here listing series originally published in the commercial US/UK publishing market. Epic in its largest sense exists as a storytelling medium worldwide.

FAYE: Speaking of writing for adults vs. YA, you have your first YA novel, Court of Fives, coming out on August 18. It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan! What makes Court of Fives YA, though Jessamy is not that much younger than Cat and Bee of The Spiritwalker Trilogy? Tell us more about working with a YA editor for the first time. Did you have to significantly alter your writing/revision process?

FAYE: Speaking of writing for adults vs. YA, you have your first YA novel, Court of Fives, coming out on August 18. It’s no secret that I’m a huge fan! What makes Court of Fives YA, though Jessamy is not that much younger than Cat and Bee of The Spiritwalker Trilogy? Tell us more about working with a YA editor for the first time. Did you have to significantly alter your writing/revision process?

KATE: Thank you! I’m just so thrilled that people are enjoying Court of Fives.

A) When, in 2008, I sent a partial of Cold Magic to my agent to let him know what I was working on next, I asked him if he thought the story was YA or adult. He said it was adult because (in his words, and I paraphrase) the story is about the world as much as it is about Cat and that in his opinion YA had to be focused on the main character(s) with the world secondary. Is he correct? I can’t really say. I do know that Spiritwalker falls in a gray area and has had crossover between fantasy and YA as well as romance.

Because Spiritwalker is very much a bildungsroman, a story of Cat becoming an adult and understanding both herself and the roles she can play in the world she lives in, it feels more like a “college age” story than a teen story to me. The world and the events going on around Cat do play a huge role in the novel’s epic scope. It’s not that YA/teen stories don’t have epic scope—many do—but perhaps it is an issue of how tightly the story wraps around the main character(s). I’m honestly not sure.

Jessamy in Court of Fives is also trying to figure out how she fits into the world around her, but I think the story revolves more tightly around her immediate struggles and how she views them.

B) I knew when I sold a YA novel that I would be revising to a somewhat different aesthetic, so I was prepared to do a lot of work. Here are three differences I have found (there are more but for space reasons I’ll just mention these):

- I’m used to long and detailed edit letters from my fabulous Orbit Books editor and her assistant but usually she just dives in with a single sentence of “this is great, now here is what you need to fix.” My fabulous YA editors (I work with a senior editor and an associate editor) include a lot more encouragement than I’m used to! Of course, the encouragement always prefaces a major revision need, so it is entertaining to read “we really loved [4 sentences explaining what and why they loved it]” followed by “AND NOW [4 paragraphs detailing all the things that need to be fixed].”

I will note that one reason they do this is to identify the things they think are working that they want to make sure aren’t lost in the revision, as well as to clarify what they understand which helps me understand what I need to do to make sure I’m getting across to readers the story/description/emotions I want to be part of the story. Clarity is hard. Doing this work has really helped me in writing adult fiction as well because it forces me to think very, very hard about how well the images and emotions in my head are coming across on the page.

- Pacing is a paramount concern in all fiction these days. Books with a leisurely pace or plot still get published but they are increasingly rare in genre just because tastes and attention spans are what they are right now. So I do have to be very focused on pacing, very conscious of not bogging down, and I make a greater effort to find ways to end chapters on a page-turning line.

- Another way this difference between YA and adult manifests is in worldbuilding. In adult SFF the writer has more room, even in a fast-paced story, to pause and drop in an interesting tidbit of world building. In YA, I have been continually encouraged to pull out extraneous description or weave it directly into the plot, so Court of Fives has given me a challenge in delineating a world with fewer words than I normally use to create the setting. This kind of exercise is really good practice for a writer like me who has been writing for a long time. It’s all too easy to fall into a rut or just coast along with the skills I have, and there is a genuine thrill in feeling pushed to gain new ways of working and new perspectives on how to unfold story. Best of all, everything I learn in whatever I write carries over into everything else I write, so all my work benefits.

C) I haven’t really had to alter my revision process except that with the YA I am doing more of the process with the editors instead of alone, and I like that. This is my basic process although I should mention there is a lot of variety between books:

- Write first draft.

- Do a major revision to sort out structural and character issues. Turn this draft in.

- Do a second major revision to editorial comments (and some beta reader comments). Send this version to beta readers.

- Do a revision for minor (nuance) changes and consistency/fixing straggler plot items. This revision includes line edits, polishing, and cuts. This revision goes to copy editor.

- Get copy edits and, besides dealing with copyediting queries, do a second line edit and final cuts (I often find things to cut at this point that were lost in the thicket of verbiage and revisions earlier).

With YA I turn in the first draft so I do all stages of revision with the editors.

I should note that every book I write has a slightly different process. Both Cold Steel and Black Wolves went through an arduous process in which steps 1 and 2 were basically conflated, and so they took a very long time to get to a finished “first” draft, which were really several major partials with backtracking and rewriting and multiple false starts and dead ends. I call these two, like The Law of Becoming, “Beethoven” books in honor of Beethoven who (according to the myth) labored laboriously over his composition. The two part An Earthly Crown/His Conquering Sword (Jaran series) and Traitors’ Gate (book 3 of Crossroads) were both “Mozart” books: They were so clear in my head that I wrote them extremely quickly and straightforwardly, and the revisions process for both of those books mostly consisted of nuance plot revisions, line editing, and cutting.

I should note that every book I write has a slightly different process. Both Cold Steel and Black Wolves went through an arduous process in which steps 1 and 2 were basically conflated, and so they took a very long time to get to a finished “first” draft, which were really several major partials with backtracking and rewriting and multiple false starts and dead ends. I call these two, like The Law of Becoming, “Beethoven” books in honor of Beethoven who (according to the myth) labored laboriously over his composition. The two part An Earthly Crown/His Conquering Sword (Jaran series) and Traitors’ Gate (book 3 of Crossroads) were both “Mozart” books: They were so clear in my head that I wrote them extremely quickly and straightforwardly, and the revisions process for both of those books mostly consisted of nuance plot revisions, line editing, and cutting.

FAYE: What fascinates me most about epic fantasy—as someone who majored in anthropology in college and loves learning about new cultures—is the worldbuilding process. You’re essentially constructing a new world, and with that, new countries and histories and customs. What is your research process like? What comes first, the details or the big idea? More importantly, since we’d all love to see more diversity in our fantasy, what is your advice for portraying cultures inspired by non-Western nations?

KATE: What comes first for me is an image of a character in a landscape, like a brief clip from a film. Often the landscape or backdrop seen in the image is based on material I’ve been reading about at some point in the last few years that has wormed its way into my subconscious. Other times the backdrop might initially be fairly generic and the most I immediately know about it is what technology level the story world will have.

Based on that image I may choose to push further into a research area I’ve already started or I may consciously think about where I want to go for the story in terms of the geographies and cultures I want to explore. I have world built “analog” cultures, which I define as “X country/history only with different names and some altered history.” I’ve also created cultures complete in themselves, unique to their space just as every culture on Earth has a unique cultural space, however small or large that space may be.

At this point in my process I will do a certain amount of reading and researching. This stage comes before the writing starts, and usually it happens while I am writing another novel. The appeal of a “side project” is strong; it’s like an illicit escape from the project you’re supposed to be working on, and the Crossroads Trilogy, the Spiritwalker Trilogy, and Court of Fives all started life as me sneaking away from a deadline to begin creating a new world. In fact, at the time of writing this answer (June 2015) I have three secret projects tugging at my skirts, one contemporary SFF and two space opera/SFs. The SF focus of these projects probably isn’t surprising considering I am currently writing two fantasy trilogies (Court of Fives and Black Wolves).

As I continue to do bits and pieces of research I will also poke at an opening scene and start some very discreet and sketchy outlining of plot. Bear in mind that no one writes exactly the same way. For me, the intersection between setting and character has always been the most important element of developing a story because the two unfold at the same time.

I do not create a setting and then place characters in it. A story kernel doesn’t come alive for me unless I have a human story to hang my hat on. That is, I have to imagine a character in a situation that has an inherent emotion or urgency or conflict that engages my passion to explore it further.

Contrariwise, I do not come up with characters and then create a setting for them.

As a brief aside: I know writers who “discover the world as they write” and those who start with a notebook already full of details. There is nothing wrong with either of these methods or any other: Writers need to figure out what works for them.

In my case, because of the way I personally integrate culture and character in my mind, I can’t create a character and story first and then figure out where it is set.

For me, people exist within a cultural space. They have beliefs, expectations, habits, and knowledge based on the micro- and macro-culture(s) they live in, and in my opinion a character is never truly created without some kind of context. A character developed before a setting has what I’ll call “invisible context,” one the writer may not be aware inhabits the character. With each choice we make about a character we invoke context even if we don’t intend to.

Let’s say I want to write a story about a young woman who is unexpectedly and against her will required to marry a man who is a stranger to her. Some may recognize the seeds of Cold Magic in this description. But look at a few of the assumptions embedded just in that unremarkable and trope-ridden sentence: That marriage exists in this culture, that a person may be forced into marriage, that people don’t need to know each other which means someone besides the two people involved are arranging the marriage. A few things we don’t yet know are whether marriage, in the culture, is exclusively between men and women, whether the male partner can likewise be required to acquiesce to a marriage he may or may not wish for, what group or individual has the power to enforce their will in this matter, and what it gains them to do so.

Let’s say I want to write a story about a young woman who is unexpectedly and against her will required to marry a man who is a stranger to her. Some may recognize the seeds of Cold Magic in this description. But look at a few of the assumptions embedded just in that unremarkable and trope-ridden sentence: That marriage exists in this culture, that a person may be forced into marriage, that people don’t need to know each other which means someone besides the two people involved are arranging the marriage. A few things we don’t yet know are whether marriage, in the culture, is exclusively between men and women, whether the male partner can likewise be required to acquiesce to a marriage he may or may not wish for, what group or individual has the power to enforce their will in this matter, and what it gains them to do so.

All of these are part of the culture that gets built around characters and an action.

As for details versus big idea, I suppose that at the deepest level the big idea comes first but for me it is discovering the details that makes a culture come alive and feel real, because it is the details of our own lives that we take most for granted which immerse us in our day to day existence.

In Cold Magic, for example, the extended greeting between people comes from my research into the culture of Mali, where acknowledging others is more important than (for example) getting somewhere “on time.” In Court of Fives a small detail like whose carriages are curtained and whose aren’t is an important detail: women from the highborn Patron class travel through the city “veiled” by light curtains on their carriages while Patron men go about visible to all, as do all Commoners regardless of gender since their concept of privacy is different from the people in the Patron class. A detail like this reveals a great deal about class, gender, and social mores, and the readers learn something about the main character Jes’s father by noticing which rules he adheres to even though he is not himself of highborn Patron birth.

For that matter, back in the day every time I read an SF novel set in the future in which women changed their names to that of their husbands I knew the writer probably wasn’t really thinking through societal change but just tacking a very specific set of cultural expectations onto their stage-set. It’s not that it might not happen (I think C.J. Cherryh deals with this in a thoughtful way in her Union/Alliance universe books in terms of alliances between spacer families), but that in these cases “custom” isn’t actually being examined; it’s just an unthought-through assumption that the whole world and history now and forever hews to the fictional universe depicted in Leave it to Beaver.

From there on out (returning to my research process) I do as much research as I have time for. I seek out general works to familiarize myself with a general knowledge base, then branch into academic work and, where possible, what people actually from that culture say about themselves and, in historical cases, wrote (usually filtered through translations). When I’m creating a world like Crossroads or Court of Fives I focus on an amalgamation of elements to create a foundation, usually people’s understood relationship to their cosmos, and build outward from there. Once I start writing the rough draft I continue to read (and possibly read even more heavily) because I discover and make up world elements as part of the writing. I often figure out fairly major world building elements in the course of writing the first draft because oftentimes characters’ actions, or the choices forced upon them, reveal the most interesting details and challenges of their world.

The process of creation is the creation, if you see what I mean.

As for advice for people seeking to write outside the culture(s) they know, I guess I would cautiously say a couple of things.

- I’m not an expert and I have made and will continue to make mistakes. Own your mistakes. Learn from them. Listen to others more than you talk yourself.

- Make room for and try not to take space from people whose voices are more marginalized than your own. Listen.

- Be humble. Be respectful. If you are going to research a culture that is not your own, listen to the voices from that culture, don’t just seek out outside views of the culture whose analysis is more comfortable for you. Ask politely, and if people don’t have time for your questions, then retreat gracefully. If they do have time, thank them and really, truly listen to what they have to say.

- No culture is monolithic. Individuals within a culture do not hold the same views and beliefs. People can have multiple ways of understanding themselves, measured against and lived within different aspects of their lives. As in rhythm, the gaps between beats are as important as the beats. Listen.

- Ask yourself why you want to do this.

- Be aware that you will be hauling your own expectations and stereotypes down this path. I don’t think we can fully rid ourselves of this baggage but we can try to be aware of where and what some of those assumptions are and try to build around them.

- Pay attention to the details, to the elements of daily life that are often derided as trivial or too unimportant for “important” fiction. I often find the best windows into other ways of living to be the day to day experiences of the world, and the habits, interactions, languages, and rhythms that characterize people’s lives. These spaces are, after all, where most life is lived.

Diversity is realism. Furthermore, speculative fiction gives us the vastest canvas imaginable, measured only against the limits of each artist’s mind. Why build a fence when we can explore the stars?

FAYE: Absolutely. Going back to women authors of epic fantasy, one major thing I’ve noticed (and now actively look for) is portrayals of romance, love and sex compared to men authors—and beyond that, queer authors. Do you also sense a difference? What was the last headdesk moment in an epic fantasy you’d read? The last fist-pump moment?

KATE: To me the most striking difference between portrayals of romance, love, and sex by men and women lies in how those aspects of the plot are reviewed and analyzed by critics and readers.

If I read an epic fantasy novel written by a man that includes a love story in a narrative that otherwise hews to clear genre conventions, I rarely see the book discussed as “a love story” or “a romance” or otherwise held at arm’s length as if slightly displeasing to the scent. A similar tale written by a woman often may be described as if the romance is the main thing the potential reader needs to take into account. Thus we get epic fantasy series described as romance-oriented and “girly” even if they are filled with political intrigue, strife, and battles, versus manly books that may have romance and love stories but are described in terms of war, conflict, and heroics.

I find this to be particularly true of stories about personal growth and change. A love story in a young man’s coming of age story, especially a story in which the female love interest acts as a reward or a life-changing lesson for him, is seen as an integral part of his maturation. But if a girl has a love interest or romantic entanglement as part of her coming of age, then often her story is labeled as a romance even if there are other elements to her journey.

Furthermore, a story about a male main character’s growth and change, or his coming of age, is often treated as a universal story that everyone can read because its lessons are applicable to all of us. But a similar story with a female lead (or a queer lead) will often be seen as a niche story applicable only to some. It’s a refreshing change to see a series like The Hunger Games marketed as a story for everyone, and while the love triangle between her, Peeta, and Gale is central to the story, the story still remains primarily about Katniss’s journey. She is positioned as someone we can all identify with.

In terms of how love stories are written, I’m not sure. I can’t speak knowledgeably about the history of the novel. I do know that for decades the romance genre has been disparaged as poorly-written and shallow wish-fulfillment, while a strong counter-argument can be made that romance novels are feminist in showing women as beings who can express female sexual desire when for so long in the Victorian and post-Victorian era women weren’t supposed to feel or display sexual desire. Romance novels set in patriarchal cultures can also be feminist in showing women making what choices are available to them.

I’m cautious about ascribing any kind of gender essentialist difference to men’s writing versus women’s writing because I think it is currently still difficult to disentangle cultural constructs of gender from whatever biological sex may or may not mean. Do fewer men write love stories from the point of view of women than women do from the point of view of men? Possibly, but I haven’t done the work to see if this is statistically the case. Are (or were) men less likely to depict women’s sexual desire in nuanced and positive and affirming ways? I don’t know. Nicola Griffith recently showed that awards more often go to works about male main characters, and that in itself may suggest that a love story written from the male point of view will be viewed differently (as more important) than that from the female point of view.

This is one reason I think stories with queer protagonists and, for that matter, all stories less bound by the male/female binary, are so important. Such stories break down what gender means to create stories in which the binary of gender isn’t the first space along which we organize our understanding of who we are.

As for recent head-desks, any story in which the male protagonist’s lover or young wife is introduced and then killed by the end of the first chapter so he can be driven to heroic levels to take revenge. That is an instant head-desk for me, and these days, more often than not, results in me immediately closing the book.

I haven’t read as much epic fantasy in the last couple of years although I’ve read a lot of great fantasy novels. I’m defining epic fantasy as cast of thousands, multiple point of view, big ticket high stakes epic vista fantasy, so I’m going to limit myself to that. The most recent epic fantasy I finished is Ken Liu’s excellent The Grace of Kings, with influences as far ranging as Homer and Romance of the Three Kingdoms. It’s set in a patriarchal society and deals with high stakes indeed—who will rule the empire—and for quite a lot of the book women are barely visible. This is frustrating at times (and some readers have been more frustrated by it than I was, so your mileage may vary), but it’s also careful preparation for the subversion Liu has prepared in the last third of the book. There’s a great scene in which the patriarchal prejudices of one character are literally used to defeat him. Fist-pump!

I haven’t read as much epic fantasy in the last couple of years although I’ve read a lot of great fantasy novels. I’m defining epic fantasy as cast of thousands, multiple point of view, big ticket high stakes epic vista fantasy, so I’m going to limit myself to that. The most recent epic fantasy I finished is Ken Liu’s excellent The Grace of Kings, with influences as far ranging as Homer and Romance of the Three Kingdoms. It’s set in a patriarchal society and deals with high stakes indeed—who will rule the empire—and for quite a lot of the book women are barely visible. This is frustrating at times (and some readers have been more frustrated by it than I was, so your mileage may vary), but it’s also careful preparation for the subversion Liu has prepared in the last third of the book. There’s a great scene in which the patriarchal prejudices of one character are literally used to defeat him. Fist-pump!

Is a shift happening? Am I seeing fewer “male journey centered” type of stories now—pausing to note that I have nothing against the male journey story; some of my favorite novels are male journey stories—and more well rounded characters from all the spaces of life? I don’t know. I hope so, and the success of YA as a genre has certainly made a huge difference even if I’m not seeing quite the same strides in adult epic fantasy (I should note there is a lot of strong writing out there now regardless of whether it fits my tastes).

Fantasy and science fiction are, after all, the literature of the imagination, and imagination is meant to be vast, not confined. I think we live in an exciting age of narrative.

FAYE: Lastly, tell us about a remarkable woman of fantasy literature—an author, reader, agent, editor, scholar, or someone else—who has changed your life.

KATE: I want to mention two women who personally helped me, in two different ways.

Before I was published, when I first got an agent interested in my writing, said agent sent a partial of my manuscript (an early version of A Passage of Stars) to one of her published clients, Judith Tarr (author of SF, fantasy, and historical fantasy), who graciously read and critiqued the first few chapters. First of all, critiquing is very time consuming, especially for a new writer who has an exceedingly imperfect grasp of the basics. So that alone is a generous act. But the critique was also brutal and absolutely compassionate because it went like this (I paraphrase): “This writer shows promise. Now here is everything wrong she needs to work on if she wants to get published.” The critique hit like ice water to the face, and I remain eternally grateful that Judy took the time to read and comment and, more than that, that she had enough respect for me as a writer to not mince words and get straight to the heart of the matter, which is that writing is hard work. It helped that she absolutely nailed my worst flaws, all of which I have improved on but which still dog me all these years later. I can’t thank her enough.

The other writer I need to mention is Katharine Kerr (best known for her Deverry series) who befriended me when I first entered the field as a newly published writer with tiny children. At that time my husband was working as a police officer with lots of overtime, and she invited me to her house every week so she could help baby wrangle the infant twins and toddler big sister. I survived their early years in large part because she became and remains family, and her encouragement and help made it possible for me to push through the toughest times. Without her I doubt I would have the career I have managed to build.

The connections we make are often what sustain us. I can’t emphasize that enough both for myself and, honestly, as a way to think about story, because story itself is a connection that forms between the storytelling and the audience. That’s what we aim for: That through an intangible magic we connect through words on a page. What an amazing thing that is.

Connect with the Sirens community

Sign up for the Sirens newsletter